101 Things people said about Zaha Hadid

Designed by Alicia

What stories, myths, and rumors encircle one of the most recognized architects [Zaha Hadid] and a major female figure in the field? And how does this reflect in the way [non]architects, architects, academics, and students perceive others who identify as female in architecture?

If you ask most [non]architectural people to name an influential woman in architecture, almost all, without any doubt, would say Zaha Hadid…

And in looking for a way to think about gender and female architects, Hadid became a catalyst for an exploration of the bold opinions linked barely if by a thread to Zaha Hadid – not the person, individual, or woman but the name, a sort of title – as most didn’t know her, really. So, this observation became about the act of collecting stories, myths, and rumors and how this transforms our perspective of an individual, how this distorts a person into a concept, and how this idea has found its way into academia and professional spaces through para-social relationships.

For some, Hadid was an inspiration and a role model. Even today, thinking beyond her distinctive design, characterized by bold curves and futuristic aesthetics, she is recognized for achieving her professional position and practice on her own, particularly during a time in which other female architects would likely partner collaboratively with male architects (who were also their husbands).

Yet, I would hear more about the myths surrounding her “questionable” lack of marital status references to her looks concerning her weight – alongside wild sexual stories surrounding an alleged red couch she supposedly had in her office – more than I would ever hear about her work or even her problematic practices during my undergraduate years in architecture school. These myths steadily permeated our studio, taking the form of analogous stories and myths surrounding my relationship and those of my female peers’, with our male counterparts. Judgments were made regarding our skills and even design intellect as only a reflection of our romantic relationships with our male partners or fellow peers. Because how could any of us women think or hope to develop any design skills if it wasn’t for listening to the “sage” advice of our partners or better yet getting them to complete our work for us instead creating/developing our own design projects?

And this may feel like an old conversation to be having, yet how many have walked around building 7 and heard the stories, rumors, and myths surrounding our female faculty? Not to say that there is anything wrong in being critical about our professors, we should. But here I’m referring more to the way in which criticism is shown, typically placing stronger critique on the behavior of female faculty despite equivalent or similar acts from our male faculty members, who go unquestioned.

Now, brainstorming how to explore my place as a female in architecture for this project/column, Zaha Hadid and the stories surrounding her came to me as if they were a ghost from the past giving me a tool that would have helped my past self and those currently facing this question.

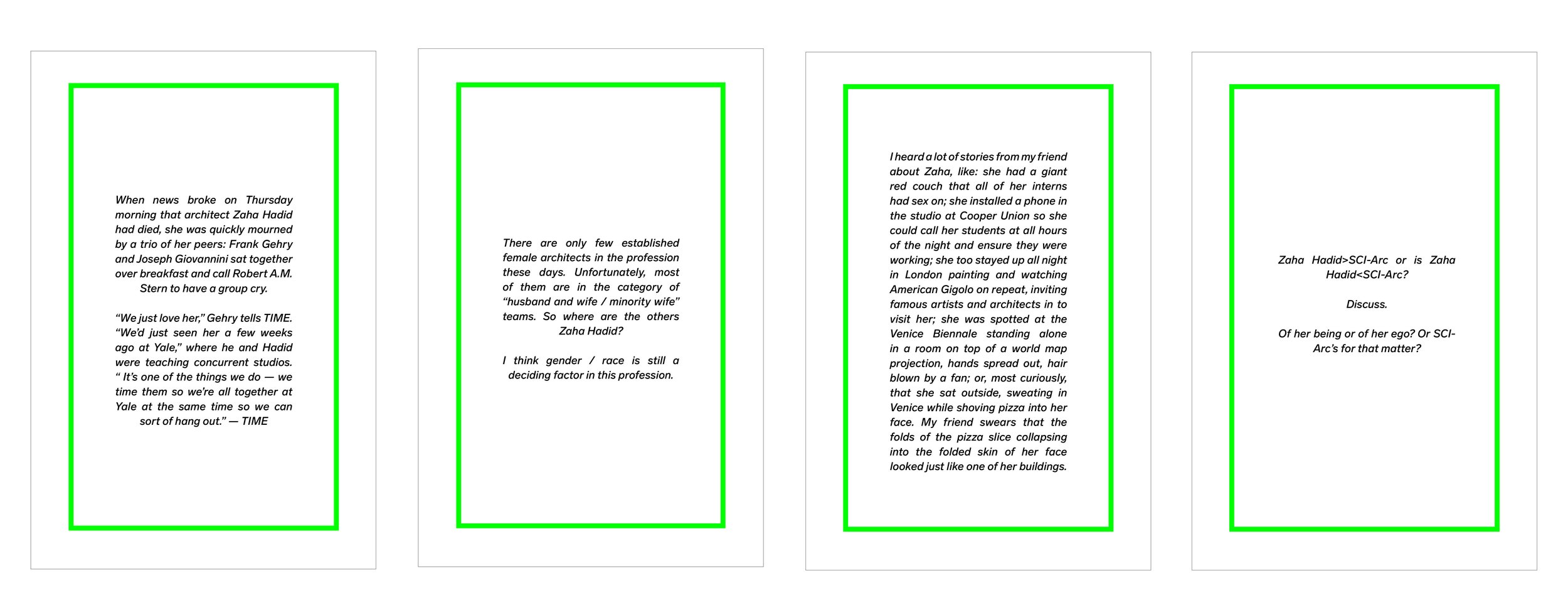

Sometime between the articles, books, and platform forums, it was as if we began reducing Zaha Hadid into a one-dimensional caricature. And, in that process of abstraction, we erase any nuances and complexities of her life and work…

… we must ask, why is this the case? Why is it so easy to be more captious of females in architecture for the same things a male architect has done? Why are female-identifying architects the ones who need to talk about the maintenance and care of architecture? Why the double-standard...and where do the comments stem from? Is it about sex, bias, gender stereotypes, etc.? How can we start deconstructing these biases? How did this communication precedent showcase into cards of words to one of the most recognized architects [Zaha Hadid] find their way into the studio space and how we interact with each other, as academics and professionals?

I end this note, not with a response but a request: to acknowledge our own biases, to be critical but also reflective, and to be kind to yourself, whoever is reading at the other end of the screen, anywhere, anytime.

written by Alicia Delgado-Alcaraz

edited by shift +w