Murphy’s Law

This holiday season, I had a foolproof plan for gifts. I would make a batch of my succulent planter lamps, and give them out to friends and family. The design was finalized, the circuit boards had been printed and delivered, and my drawers were stocked with the electronic components I would need. Easy enough, right? All I needed was for nothing to go wrong. But, if the existence of Murphy’s Law tells us anything, it’s that that is simply too much to ask for. The 3D printer I built a few years ago, which had been running nonstop ever since, suddenly decided to go out of commission with extrusion issues. It was a straightforward enough repair - I would swap out a few components and be back in business. But where’s the fun in that?

The planter lamp in question

You see, I’ve been itching to build another 3D printer. Inexplicably, I always come back to chase that same thrill - watching the machine that you breathed life into, breathe physical form into an idea. It’s a really beautiful process to me, a lineage of creation. I can trace the parenthood of printed parts back several generations of printers, each printer printing parts for its replacement as the design meandered and improved over the years. But this time, I would be inserting new genes into the pool; Formlabs gives me access to their industrial-quality SLS machines, so the printed parts would be coming from work. But before I could print, I had to sit down and draw up the printer itself.

Designing a 3D printer is a game of tradeoffs. The only end constraint is that something that deposits material should be able to move in the X, Y, and Z axes, so there’s an enormous amount of freedom in what the machine will look like and how it will work. There are powders and resins and solid filaments to choose from as print materials, leadscrew and belt and linkage-based motion systems, and the age-old question of specialized expensive components vs cheap off-the-shelf parts. Print speed, print quality, and printer cost are most certainly related, but not necessarily in a “pick two” sort of way. Pricier components might make for a more precise machine, but cheaper components don’t necessarily push the quality in the other direction -- there are clever design tricks and electromechanical pairings that bring down the overall complexity (and cost) of the machine without sacrificing print quality. Elegance reigns supreme: less parts means less cost and less things that could go wrong. And so it was my goal that this new printer would be free of all vestigial structures, a brutalist approach at moving an extruder in three axes.

a rendering of the Y axis assembly

I started by sourcing the components I would need - motors, fasteners, electronics, and bearings. With those (and a pair of calipers) in hand, I could get to work in CAD, modelling all of these components as reference for when I would be designing the parts that constrain said components to one another. A few hours (and coffees) later, I was looking at a rendering of what the new printer would look like assembled. And she was beautiful. The needed parts were printed at work (thanks Formlabs!) and the printer came together in an afternoon. A day-long software hiccup later, and she was ready for her first test print.

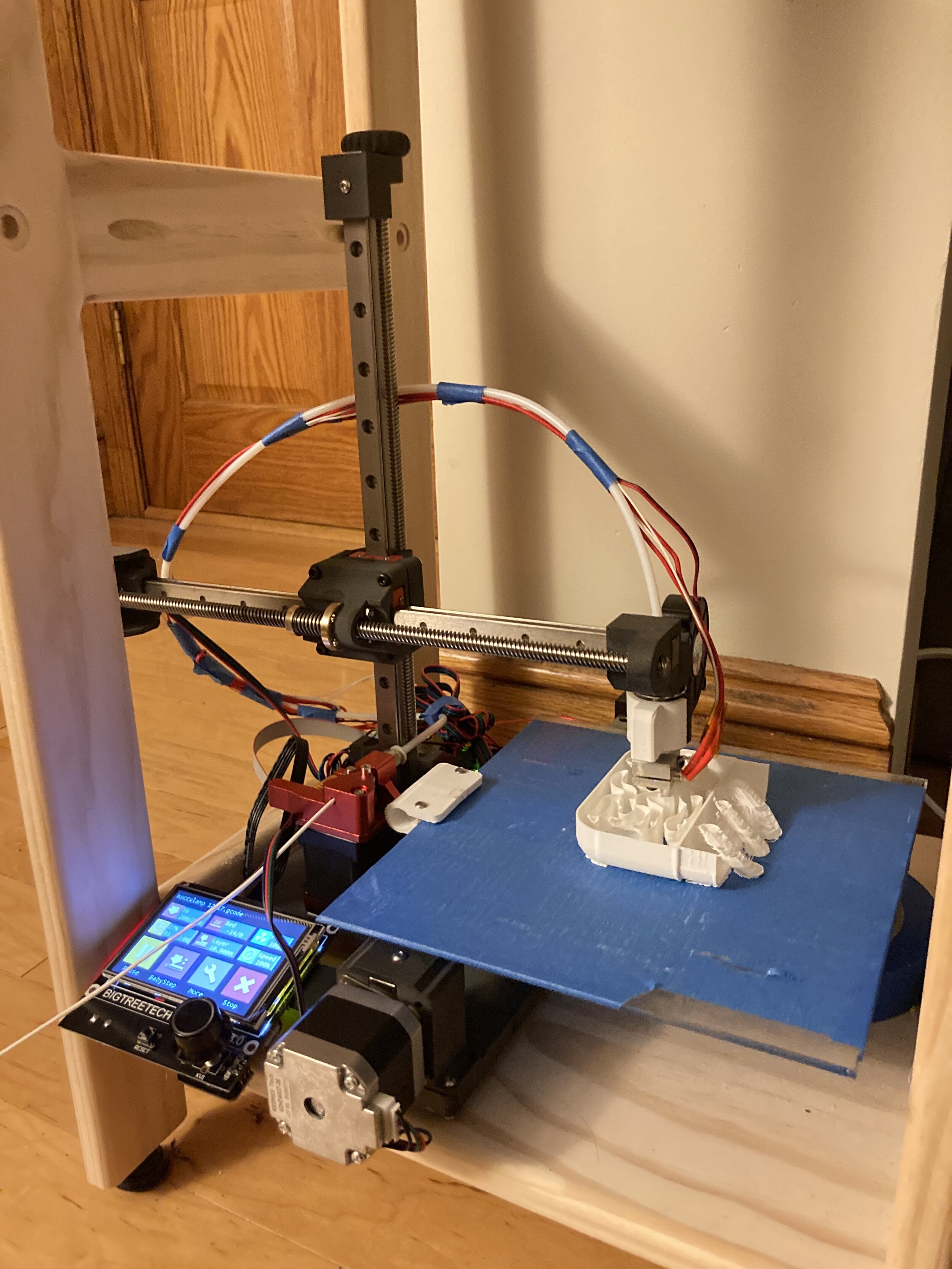

planter lamp manufacturing with the new printer!

3D printer test geometry is a whole world unto itself. Want a quick test that tells you how accurate your printer is? Try a 20mm calibration cube. Want a detailed print that shows you fine feature resolution? Try the ever-popular Yoda bust. Want a challenging print that illuminates what tweaking needs done to your print settings? Try Benchy the tugboat. There are online forums full of people debating the merits of each approach and collaborating together to improve the amount of information you can learn about your machine from a single print. As a fan of the classics I opted for a 20mm calibration cube, and some thirty minutes later I was holding it in my hand. The print finished successfully, but revealed that the clamp that held the print bed in place could use some adjustment. A few changes to the CAD later, and the printer was ready to print the upgraded part. This, to me, is the most interesting of processes - a machine making its own replacement part. And if that part doesn’t do it? Just print off another. There are no limits to how far you can customize and tweak a printer, iteratively using it to improve itself until you converge on some ideal version of that given machine. Carbon-based life forms might evolve over vast timescales, but 3D printers can optimize themselves in the span of a few hours.

And so, my journey of making a thing that makes things drew to an end, and I was ready to print off parts for my gift lamps. In fact, I’m sitting here right now, watching the newly-minted machine dance its additive dance, layer by layer giving form to a part that will turn into the main body of a planter lamp. With several hundred layers to go, I’ve got time to watch and think. And I’ll think -- about the inexperienced but incredibly excited me that started down this path over half a decade ago, about the growth I’ve seen in myself as a designer since then, the growth I’ve seen in myself as an artist since then. When I agreed to make Transience a biweekly column, I thought I would be holding myself accountable to make more art. After all, that’s the whole premise of this series, the stated summary of my intent when contributing to Out of Frame: a design student on leave reflects on life and a series of computational art. Calling a CAD model of a 3D printer computational art might be a stretch, but the process -- the inception, the refinement, the actualization, -- certainly runs parallel. There’s vision in deciding what the overall layout of the printer will be, and craft in bringing that concept to fruition. And, if you couldn’t tell from my glowing review of additive manufacturing technology, a whole lot of passion.