Automated Loom Part I: it begins with a duck

An Introduction to Interlaces/Interfaces

While we are constantly surrounded by textiles, their full impact is often overlooked. This industry and its technological innovations have had a profound impact on the world.

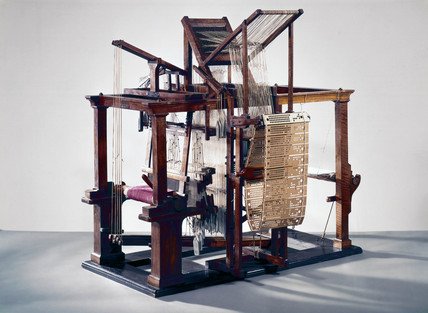

Knitting has taken on a new persona, being linked to concepts of the digital (digital knitting, cnc knitting, 3D knitting). Current architectural and computation terms are being redirected at this textile process. And yet, the linkage of computation to textiles is not a new concept. Specifically weaving technology, can be considered the origin of all things computation. The weaving machine or loom holds the key to these fundamental systems.

This column will look at the history of the loom, highlighting the connections formed between textile innovation and larger technological histories. From the local (New England, MIT) to the global.

Automated Loom Part 1: it begins with a [pooping] duck

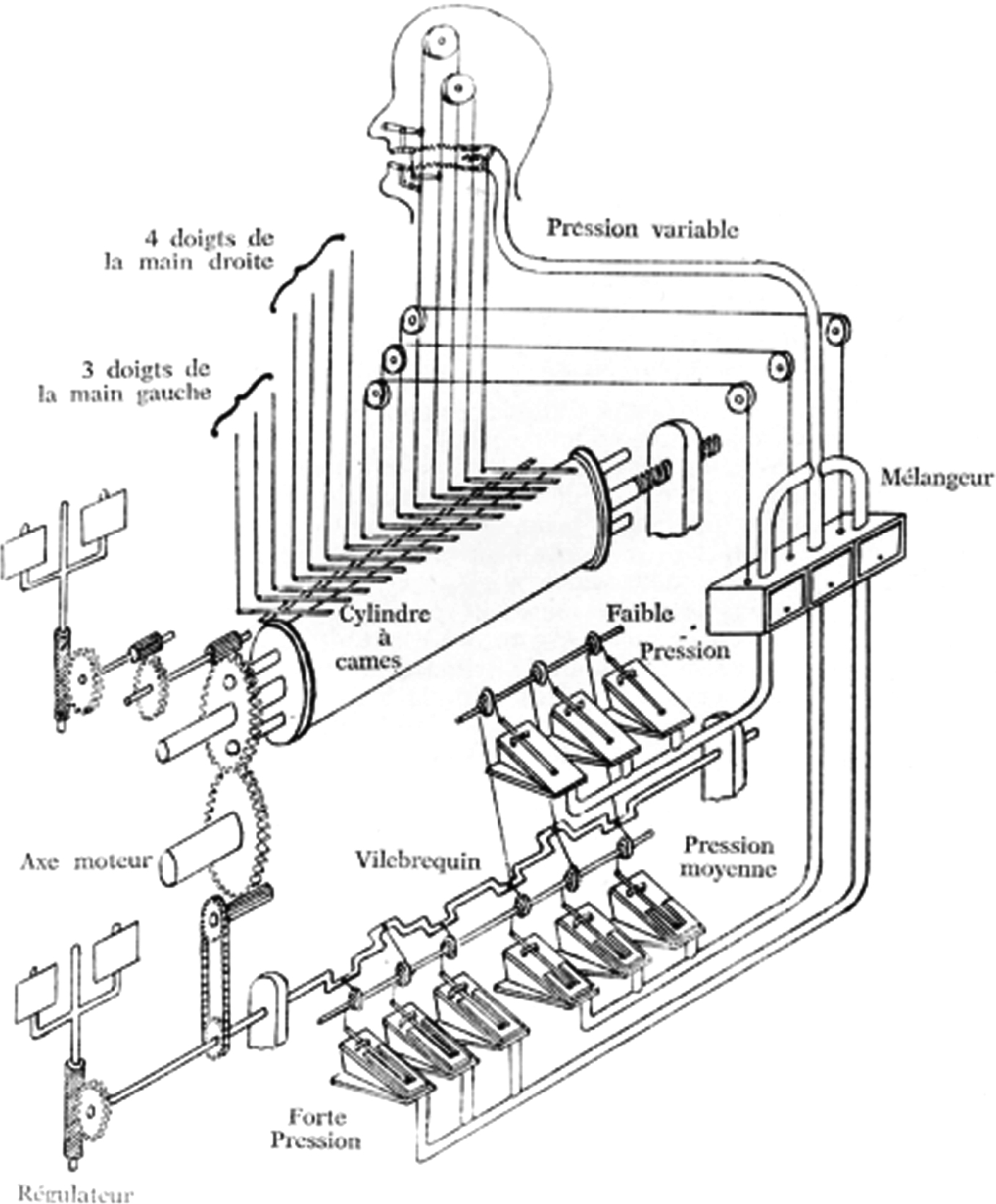

Our story begins in 18th century France with a man named Jacques de Vaucanson. A perpetual inventor, Vaucanson spent most of his career in Paris designing mechanical toys. In 1738 Vaucanson displayed his Flute Player in his shop window: a life size robot standing five and a half feet tall. Invented with the purpose of public entertainment, (a foreshadowing of the robot’s replacement of humans) the contraption had three mechanized parts mimicking the tongue, the lips and human breath. The idea of the Flute Player was exciting to the people of Paris, but unfortunately its performance was subpar in comparison to the real actions of a human flute player.

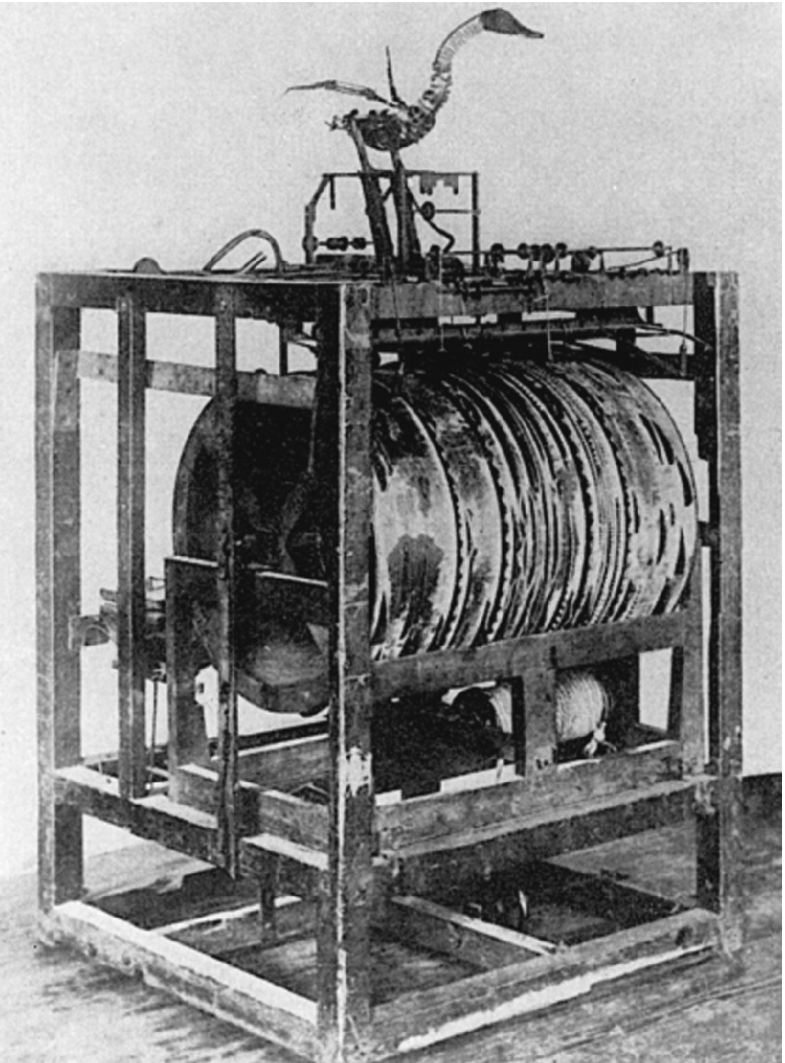

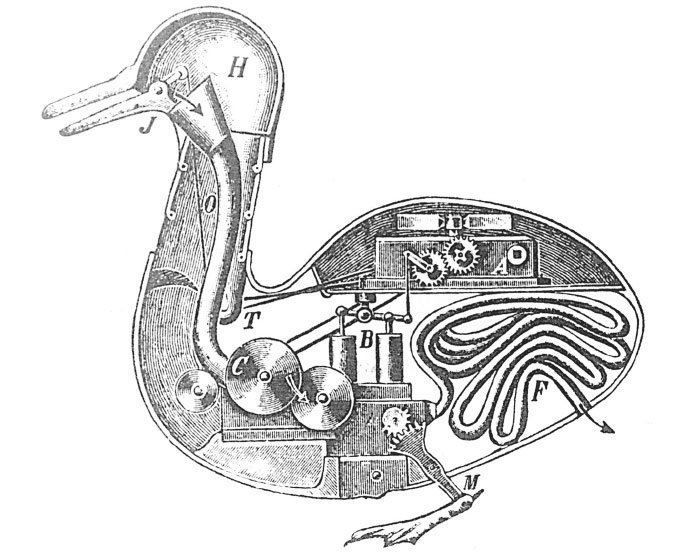

Although somewhat of a failure, the Flute Player did not stop Vaucanson from continuing to invent. He next set his eye on the digestive tract, inventing the Pooping Duck (also known as Digesting Duck, Shitting Duck, and Defecating Duck). Made up of 400 moving parts the Duck was a mechanized creature that had the ability to move its wings and digest food in a scientifically legitimate way. (Later revealed duck maneuver was merely a hoax.)

Vaucanson applied the mechanized tensioning systems from the Flute Player and Pooping Duck to looms designed by Basile Bouchon in 1725 and Jean Baptiste Flacon in 1728

Basile Bouchon, a textile worker in Lyon and son of an organ maker, used the cylinder mechanism of a barrel organ as the main structural system of his loom. The cylinder was wrapped with a perforated paper tape, this tape controlled the movement of warp ends. This system allowed for a hands-free control, but only allowed for simple and short weave structure patterns. The type of paper used made it difficult to change and revise patterns quickly.

Three years later, Jean Baptiste Flacon replaced the continuous paper for perforated linking cards and extended the width of card, allowing for more complex weave structure. Both Bouchon and Flacon’s loom had little success. It was not until Vaucanson that real improvement became visible. Changing the location of the perforated card system to the top of the loom, Vaucanson was able to eliminate a series of weights, cords, and pulleys. The tensioning system from Flute Player helped solve issues of warp end snagging and increasing number of yarn colors used in both the warp and weft. Not without issue, these updates were by far the most productive yet. The Lyonnais’ weavers were not pleased with the innovation, resulting in protests on the street in which stones were thrown at Vaucanson.

If not for textile workers’ objections, Vaucanson would have continued innovating the loom. Instead, the job was taken on by another inventor. Fifty years later, Joseph-Marie Jacquard, will become the namesake to the most revolutionary loom to date. More to come in Part 2.

References

“Jacques de Vaucanson- Complete Biography, History and Inventions.” History-computer.com. January 4, 2021. https://history-computer.com/jacques-de-vaucanson-complete-biography/

Sennett, Richard, The Craftsman (Yale University Press, 2008), 86-89.

Wang, Yanyu. Distinguished Figures in Mechanism and Machine Science. (Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 2020), Chapter 2.

Wayland, Elizabeth Barber, Women’s Work, The First 20,000 Years (Norton paperback, 1994)

Images

Wang, Yanyu. Distinguished Figures in Mechanism and Machine Science. (Springer Nature Switzerland AG, 2020), Chapter 2.