The (Context) House 2

Is there any hope for the context house in architecture?

Arguably, the Japanese home is the most popular “context house”, often lauded or fetishized in both popular and academic architectural writing throughout the 20th century, and to the present day. In one of the first English language accounts of Japanese domestic architecture, Japanese Homes and Their Surroundings, zoologist and incidental anthropologist Edward Morse offers a loose survey of homes he encountered in the mid- to late-19th century.

Standing in the tea room of a Japanese merchant, Morse’s curiosity was piqued by distinctive Chinese influences on its design. Along with a sketch of some of these features, he offers this thought:

Whether [the owner] had got his ideas from books, or had evolved them from his inner consciousness, I do not know; certain it is, that although he had worked into its structure a number of features actually brought from China, I must say that in my limited observations in that country I saw nothing approaching such an interior or building.

What intrigues me about this moment is not so much Morse’s assessment of design’s authenticity, but the mechanism by which they end up in this house. See, for this to have happened, the house owner must have 1) either seen an in-situ example or some representation of Chinese architecture, 2) borrowed from this mental image of a “Chinese Architecture”, and finally, 3) translated that image into a physical detail.

When you think about it, this is not unlike Geertz’ description of the process of understanding a wink. It requires a thick description; an understanding not just of the physical attributes of the object, but its context, to create an informed guess at what its creator’s intentions were.

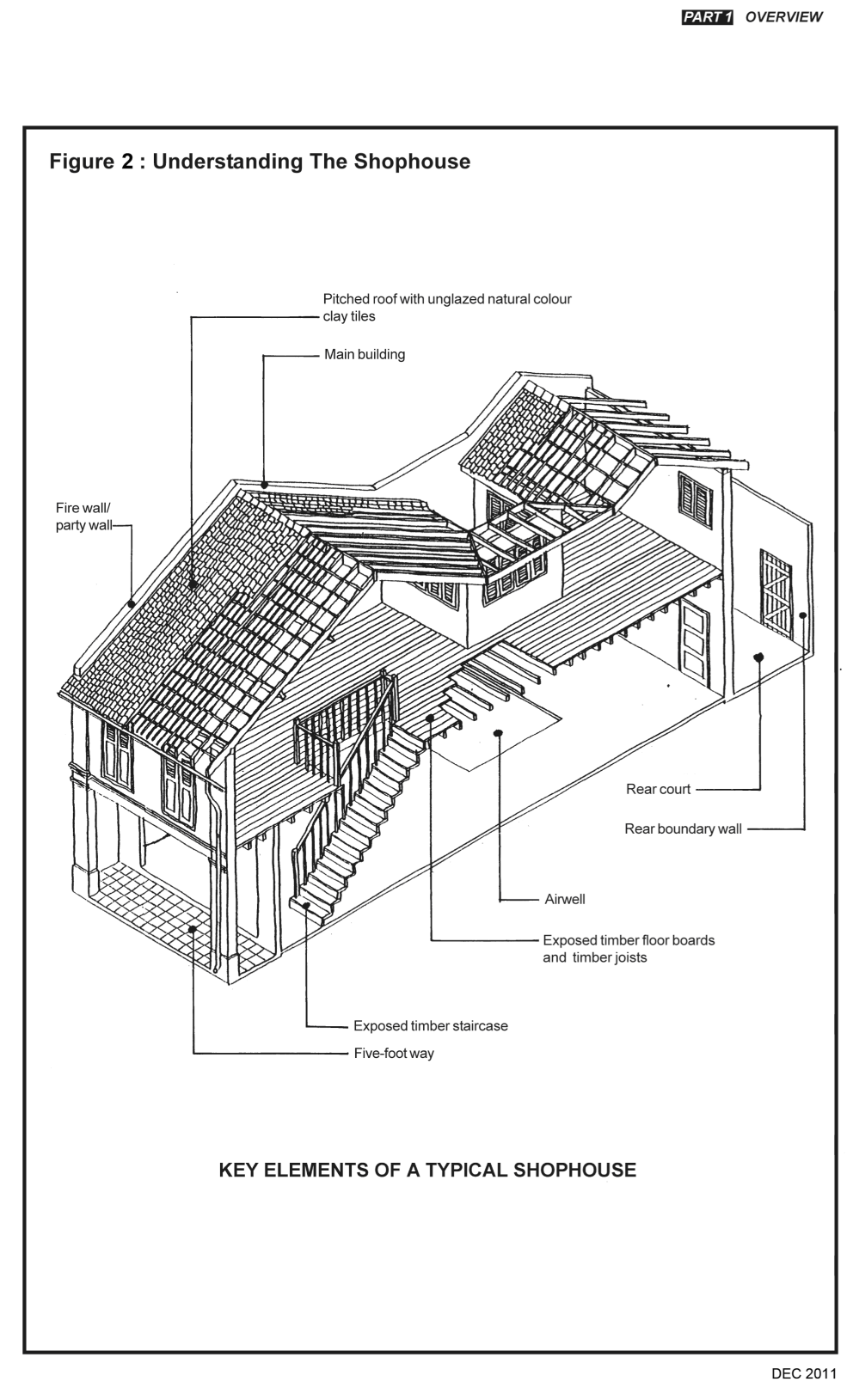

Understanding the Shophouse. Exposed Axonometric by Singapore’s Urban Redevelopment Authority. Source: https://www.ura.gov.sg/Corporate/Get-Involved/Conserve-Built-Heritage/Explore-Our-Built-Heritage/The-Shophouse

What might a thin description of the shophouse look like?

The Singapore Shophouse is centered on an interior courtyard and a flight of stairs that connect two or three stories. Relatively narrow, the buildings tend to be around 6 meters wide and 20 or so meters long. This results in a building with really only two facades, with the front facing a public street, and the rear, a shared back alley and the back of another row of shophouses.

The deep frontal facade of the shophouse is probably its most recognizable feature, where a shop on the first floor typically spills out onto a “five-foot way”, a sheltered public walkway that cuts across the front of all shophouses. Shuttered windows on the second and third floors usually serve to signify a change to more private commercial or residential spaces.

Most distinctively, the front facade is usually highly ornamental, adorned with elaborate plasterwork and colorful tiles, alongside carved wood shutters and doors. This ornamentation could well be the subject of an entire series of essays, for all its mixing of styles and motifs; it is hard to imagine someone taking a look at these facades and declaring that they are unequivocally “Chinese”.

The rear of the shophouse reveals a slightly different architectural narrative. Before the advent of modern plumbing, the narrow back alley would have been used by “night soil carriers” for the disposal of waste, but today, they also carry a different infrastructural purpose. Any wandering visitors to these back alleys will also hear the unmistakable drone of dozens of stacked air conditioning radiators, fans and ventilators which are considered essential for modern, tropical living.

360 Video of a walk down a five-foot way. Video by Author.

To return to the idea of authenticity and “Chinese-ness”, I would like to focus on just one of the distinguishing features of the shophouse, its “five-foot way”. Often associated with the Raffles Town Plan of 1822, its implementation was part of a larger overhaul of urban planning in Singapore by none other than her fabled British “founder”, Sir Stamford Raffles. Although not directly invoking the term “five-foot way”, the guidelines stipulated for sheltered verandas on both sides of the street that connect to form a continuous passageway. This would eventually take the form now seen in Singaporean shophouses, but also all over Southeast and South Asia.

Does this description of it make it seem more “legitimate” for you? That it has an established origin and place in history?

As pointed out by Simon and Emrick in The demise of the shophouse, the attribution of this detail to Raffles’ guidelines is somewhat incomplete. The sheltered walkway in this typology apparently predates this, with recorded examples from the late 18th century in present day Jakarta and Chennai. In stating, and restating, this factoid though, we become much more convinced of this characterization of it, and less concerned by the details of its authorship and subsequent translation to other contexts. In a way, its origin is being rewritten, with colonization as its protagonist.

The interesting thing about following this line of thought, is the geographical trajectory it sends us along. Through the perspectives of different authors, the five-foot way becomes an instrument for something else altogether. Jon S.H. Lim, writing for the Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, closely relates the five-foot way to the identity of the shophouse, using the same 1822 Ordinances as a means to characterize the typology as follows:

“Through building by-laws under the British, it became a Malaysian prototype which gained influence in many Southeast Asian and Chinese cities of coastal China.”

As a Singaporean, this is somewhat of an amusing statement to me as Singapore and Malaysia have a rather rambunctious history when it comes to staking claim to certain regional things, especially foods. To brand this typology as “Singaporean” or “Malaysian” seems to me more about larger national and cultural narratives than it is about the architecture itself. It is intriguing that Lim also credits Fujian, China as the origin for the Hokkien word for shophouse, but stops short of a comparison between the physical architectures, instead calling the Fujian architecture a “business house”.

Yet, in Southern China, the shophouse is seen in a completely different light. In the essay Rise and Fall of the Qilou, Jun Zhang picks up on this journey of the five-foot way, from the Raffles Ordinances, to the rest of Southeast Asia, then up to Southern Chinese qilou in the early 20th century. Typologically, the qilou is nearly identical to the Southeast Asian shophouse, yet, Zhang offers us some insight as to how its reception changed over the decades.

In the 1930s, the qilou served a similar purpose to the Raffles Ordinances of 1822; they were the face of modern urban planning, representing new forms of commerce and property. Post-war, however, this same association painted a target on the shophouses, for they become synonymous with the ills of capitalism. The Guangzhou government, for example, would take ownership of many of these qilou, with the alleged purpose of reforming the rental housing market that these buildings supported.

The five-foot way, with its blending of public and private space, however, defied categorization and control, offering a blurred boundary where private and social life could take place at different times of the day. In the cramped living conditions of the post-war years, private and commercial life would often spill out into these corridors, much like how it still does with shophouses in Southeast Asia today. Zhang goes as far as to say that this feature would be so distinctive as to contribute to the “nostalgia” that comes to be associated with qilou later in the 20th century.

Together with the visible co-mingling of local and foreign elements in the facade, this distinction from the rest of the urban fabric would allow for varied new interpretations. Qilou would once again be the face of commerce in the 80s as China relaxed its stance on private commerce, it would be reinvented by some as a unique regional typology, whilst to others, it would become an unmistakable symbol of the historical friction between China and the West. In these new geographical and temporal environments, the shophouse has become something else altogether.

Qilou facades. Zhang, Jun Source: Zhang, Jun. “The Rise and Fall of Qilou: Metamorphosis of Forms and Meanings in the Built Environment of Guangzhou.” Traditional Dwellings and Settlements 26, no. 2 (January 2015): 25–40.

In this brief look at just one element of the shophouse and its journey into new contexts, I hope it becomes evident that the interpretation of architectural objects matter just as much as the physical attributes we observe in them.

To again borrow from anthropology, this time from Anna Tsing’s The Global Situation, perhaps it is more informative to trace the landscapes over which architectural objects move, alongside the changes in the objects themselves. To acknowledge that translations and interpretations are as important as concerns of historical and cultural origins, or of typologies and characterizations.

Even in acknowledging this interdisciplinary approach, I believe that the real question it returns to architecture is one about the nature of our theories and our pedagogies. One of Geertz’ conclusions is that anthropology should seek a low-lying kind of theory, one that does not depart too far from its milieu and subject of research. What then of our world-encompassing architectures? Of architects who claim authority to build just about anything, anywhere, and at any time?

//

It has been hard to write all of this without acknowledging the many recent events in America, and across the West, of anti-Asian sentiment and, often, violence, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. Asian neighborhoods, Chinatowns, and most recently Asian massage parlors, have all become bizarre heterotopic foci for racist rage, and an increased “othering” of Asians and the various Asian diasporas. Or have they always been that way?

Lim, Jon S.H. THE 'SHOPHOUSE RAFFLESIA': AN OUTLINE OF ITS MALAYSIAN PEDIGREE AND ITSSUBSEQUENT DIFFUSION IN ASIA, 264, 66, no. 1 (1993): 47–66.

Morse, Edward S. Japanese Homes and Their Surroundings. New York City, New York: Dover Publications, 1961.

Urban Redevelopment Authority. The Shophouse. Urban Redevelopment Authority. Accessed March 23, 2021. https://www.ura.gov.sg/Corporate/Get-Involved/Conserve-Built-Heritage/Explore-Our-Built-Heritage/The-Shophouse.

Zhang, Jun. “The Rise and Fall of Qilou: Metamorphosis of Forms and Meanings in the Built Environment of Guangzhou.” Traditional Dwellings and Settlements 26, no. 2 (January 2015): 25–40.