Call and Response - Procedure

Precision was valued long before the invention of CAD and any machinery that responds to triple-coordinate positioning code.

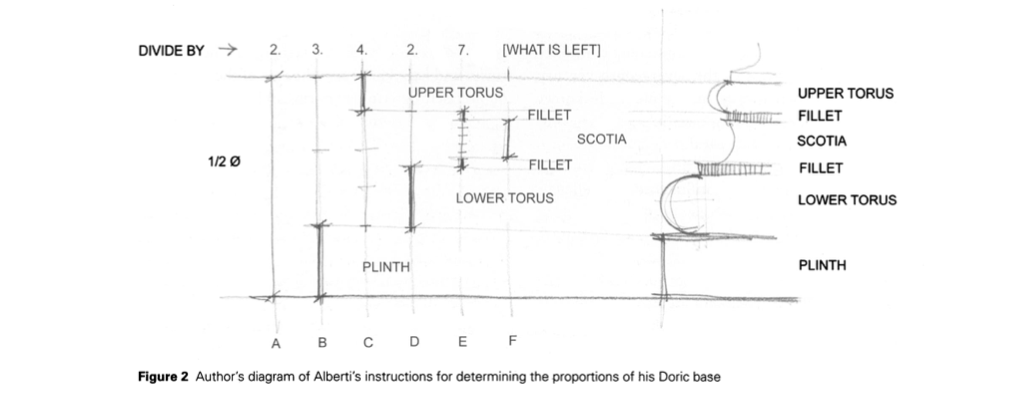

The system of architecture described by Alberti in 1485 is based entirely around precisely determined norms and standards, where every component has a recognizable form and a name, and the assembly follows strict rules. He described most elements through a series of proportions and “units of measurement were derived from parts of the building itself” (Carpo), typically a column.

Alberti’s treatise, De re aedificatoria, provided a method that was defined and disseminated in writing rather than handmade drawings, and was a technical manual and theoretical argument in one.

LEFT: Leon Battista Alberti, L’Architettura…tradotta in ligua Fiorentina da Cosimo Bartoli…con la aggiunta de Disegni (Florence) 215; RIGHT: AutoCAD dimension string, author’s screenshot

These algorithms, or codes for design, had one possible outcome- and they warned against deviation (error) from what was put forth as the right answer to a set of questions. They propose an already finished product by way of a rigorous method, with no middle. The drawing created is already a finished product before it is drawn.

Mario Carpo, “Drawing with Numbers,” 2003.

“This study of the increasing complementarity of drawing and computing in early modern architectural theory may shed light on the more general issue of the relation between technologies of quantification and the making of architectural forms––a long history of mutual interactions that is now going through another phase of rapid change.”

Still, there is an unseen middle phase in the process of most human things. Francesca Hughes likens the struggle between ideas and matter in buildings to the hesitance for artists, scientists, and philosophers to draw embryonic development in the 14th and 15th centuries. Jacob Rueff in 1554 depicts a “cotton-candy-like fluff gradually developing a network of arteries, which slowly draw the form of a perfect baby out of the amorphous material.” And “even master draftsmen (among them Alberti and Dürer) whose new techniques were used to survey everything and anything could not, would not, draw the developing fetus but instead the child to be; as if they simply could not register the form of what was on the dissection table before them.” (Hughes)

Likewise in architecture, there is an “awkward generation of drawings that immediately follows the concept sketch, the not-yet buildings and the buildings-to-be––the drawings we are never shown[…], or the drawings that are too ugly to draw.” (Hughes)

Today, even concept sketches are often manufactured after a project has been built (to prove ideological continuity? for a monograph?), and students often feel like we are wasting time if we are not working on something that is “final”. There is hesitancy around processing, around showing that we do it, around admitting that ideas change and grow up.

Mid-process façade study for Core 3 studio

This collaboration between myself and my modified desktop CNC moves an idea between the digital and physical, with some welcome feedback in translation. Moving back and forth is a process (one that is fast, fun, and surprising), and is why I keep coming back to lines. In our drawings, lines are the primordial, cotton-candy fluff that enter their awkward phase when they start to group together and overlap, or when the process starts to become the middle space where error is most welcome, and entirely useful.

Or maybe they enter the middle space as soon as they leave my computer? They are translated first into g-code, processed by the Tiny-Z’s controller board, then drawn onto paper - is this transformation itself the same kind of middling? This process too might be the proposition of a finished product before it is drawn, where the code is final, but the machine’s feedback is what makes it middling.

Mid-process façade study for Core 3 studio

References:

Carpo, Mario. “Drawing with Numbers: Geometry and Numeracy in Early Modern Architectural Design.” Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 62, no. 4 (2003): 448–69.

Hughes, Francesca. The Architecture of Error: Matter, Measure, and the Misadventures of Precision, 2014.