A Good Copy:

Craft, Context, and the Ethics of Reproduction

by Jin Zhenghua Li & Cheng Qin

对原初、理想状态的再现需求,促成记录的本能冲动——记录即再现:文字是观念的再现,图画是对现实景象的再现,曲谱是对声音组合的再现。再现催生复制、传播、生产——达成原初价值的实现。在对原初精明或笨拙的诸多模仿中,一般性记录谨慎地提取原初的核心、尊重的概括,真诚的抽象;但是,有一种记录——山寨却漠视原初的贞洁,珍贵,与神圣, 用直接,不关心,甚至看似粗鄙的方式进行对原初价值的交付。与任何自然发生行为一样,这种自发的、非官方的再现和复制是源于边缘空间对原初价值的需求,又缺乏对官方记录的获取,而产生的补充性繁殖。

Figure 1. Window of the World in 2008, Shenzhen, Photo: Yu Haibo.

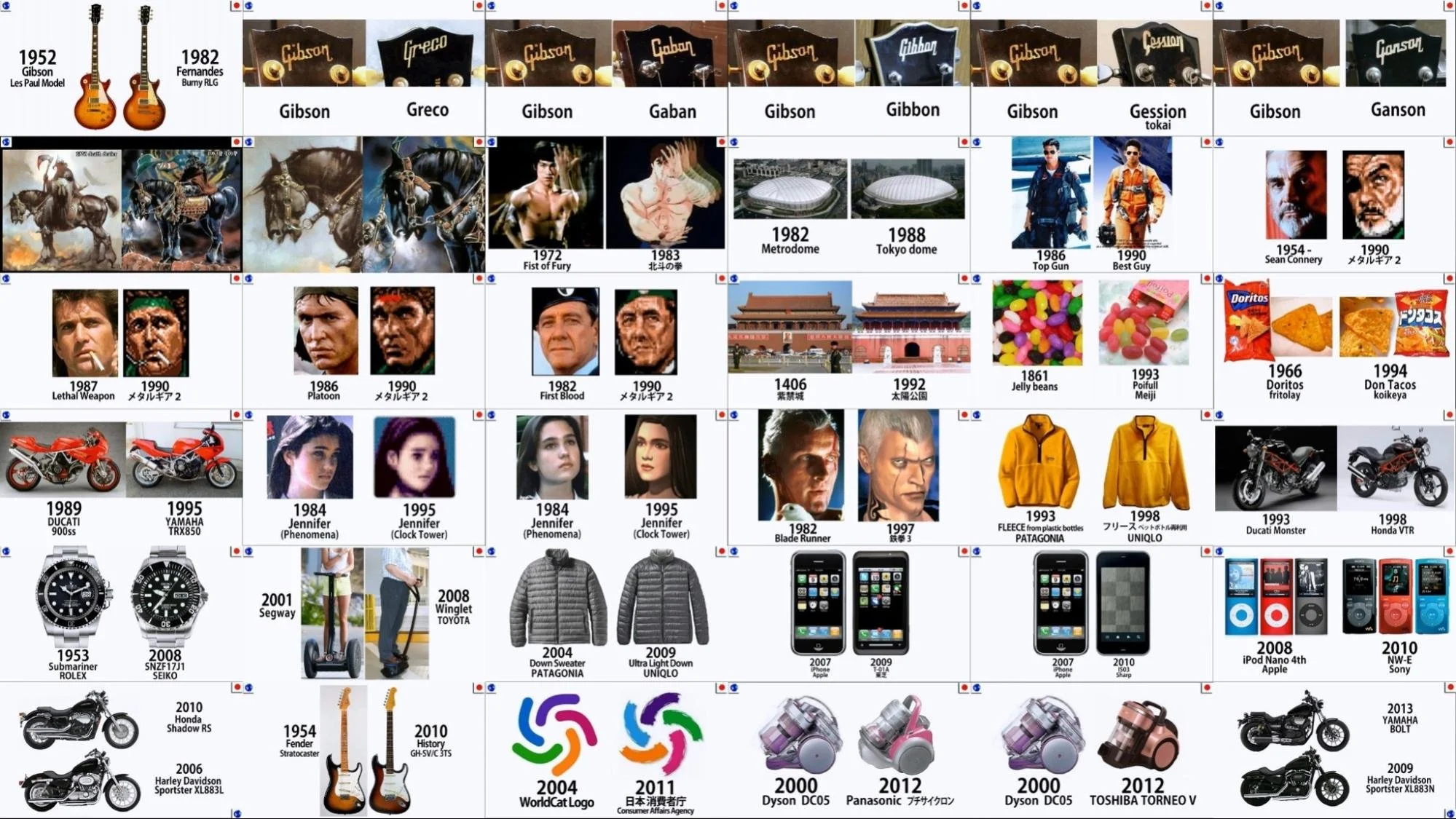

The terminology "Shanzhai" originates from the market being flooded with imitations produced by low-cost workshops in the Pearl River Delta and the Hong Kong-Macao regions, leading to social issues and drawing concern. Shanzhai’s literal meaning is Mountain(Shan-山) Stockade(Zhai-寨), referring to the remote community in the mountain. The factories that are defined as "Shanzhai factories" and the products they counterfeit are called "Shanzhai products" or Shanzhai in short. In common parlance, "Shanzhai" implies fake products, considered low-quality, copyright-infringing, and unattractive inferior copies, representing laziness, absence of design, and absence of spending effort on production. Still, Shanzhai is not a new invention of these Guangdong entrepreneurs or even Chinese, it happens in the rising region, where their economy and capabilities are growing and seeking further development. These product’s idleness, ugliness, cheapness, and poor quality may fulfill an overlooked societal demand.

Shanzhai represents the peripheral, folk, and grassroots as a complement and counterbalance of the official, certified, and elite, supplementing and harmonizing their monopoly. Shanzhai challenges the exclusivity of the upper class, emphasizing sharing and replicability, providing a de-standard means of reproduction that reconciles standardization and contextualization. Moreover, the legitimacy of the origin relies on its concept rather than its substance. It sustains itself through restoration and promotion, which alter the original substance's inherent state. By virtue of this, the essence of the original is conceptual rather than material. Shanzhai, as a reproduction of the concept from the genuine, may share legitimacy with the origin.

In a landscape of perpetual change, the immutable essence of being—authenticity—remains elusive. In Chinese culture, where Becoming serves as a methodology, the values of adaptability and situational flexibility influence various practices in Chinese culture, art, and politics. Shanzhai, as a concrete version of Becoming, is a localized manifestation and a contextualization of universal ideology. Furthermore, Shanzhai distributes value to marginal areas that are otherwise unreachable, allowing marginalized subjects, commonly neglected by universal values, to become self-sufficient. Just as a 假肢 (prosthetic limb) is called 义肢 (justice limb) in Chinese, the "fake" can, in its own way, become a form of "justice." Substitutes replicably fill in the void of identity, body, and spirit, bridging the gap between normalcy and disability and advocating for social equity, that is customized rather than identical. Hence, the concept of the cyborg suggests that an imitation can transcend mere replacement, becoming an enhancement. A cyborg is not just a mirror of the original but a reimagining, striving to surpass it rather than simply replicate it. In this light, Shanzhai, as a reflection of the original, may have already surpassed the original's value. Shanzhai will fill in the modernist folding of the original. Or, as Bruno Latour says, we have never been modern.

Figure 2. A list of Japanese copycats in a wide range of industries https://qph.cf2.quoracdn.net/main-qimg-88a9d186f56db1214ab8fb83eaa2fa02-lq

Shanzhai as periphery reproduction

Shanzhai initially referred to communities established by marginalized groups in remote mountainous areas, characterized by self-organization and anarchy, serving as grassroots organizations that restore and supplement spaces beyond the reach of central power. It is the exact relationship between Shanzhai factories and regular manufacturers: center and periphery, established and restorationist. The prosperity of Shanzhai stems from the imbalance in supply and demand caused by the centralized production of genuine products. The limitations in production capacity and constraints in intellectual property result in an insufficient supply of products, leading to higher prices and stagnant functionalities. These factors, in turn, encourage the spontaneous emergence of Shanzhai factories, which fill the void by producing affordable and multifunctional products.

In Chinese culture, where Yin and Yang seamlessly intertwine, the center and the periphery, Miaotang (庙堂) and Jianghu (江湖, the government and the folk) are two sides of the same coin, inseparable and mutually complementary. Central institutions represent orthodoxy, authority, and exclusivity, while the Shanzhai, belonging to folk forces, represent idleness, freedom, and accessibility. These two forces rise and fall: in the early stages of a dynasty, during times of unification, the centralized power's orthodoxy eliminates noise to ensure the legitimacy of its authority; whereas, when legitimacy is established, and society prospers, requiring cultural diversity, the unorthodox peripheral folk culture grows in the gaps between the censors, by replicating the excellent parts of the orthodox culture into various versions while also creating a diverse culture distinct from the orthodoxy. Therefore, Chinese society's center and periphery are not mutually exclusive or black and white but exist as complementary and transformative poles, each enhancing and reshaping the other.

Yet, Shanzhai is not merely the 'folk' but the next act in our cultural odyssey. Imagine labyrinths: the stern uniformity of power reflects the single, unbending path of the Cretan maze; the vibrant diversity of the folk echoes the intricate, winding Baroque maze. Shanzhai, however, is the Borges labyrinth, a realm of boundless and chaotic splendor. These metaphors weave a continuous tapestry. Uniformity dissolves into diversity, which births chaos, necessitating a return to order. Peripheral whispers rise as an avant-garde chorus, challenging the central symphony, only to be embraced, transformed, and crowned as the new dominion. Shanzhai becomes an authority.

The nobility and uniqueness of the genuine and original possess exclusivity and singularity, conferring a distinct status of the upper class. Protecting the genuine is protecting power. The right to define fake and counterfeit comes from institutions' obsession with preserving the uniqueness of the genuine, thereby reinforcing social hierarchies and injustice. In other words, the exclusivity of genuine products rejects the sharing of values, limits reproduction, and denies social equality. In pursuing social fairness, the replicability and reproduction of experiences, particularly an adaptable and situational reproduction is crucial. Shanzhai is one of the emerging methods that harmonize replication and situational adaptability in production.

Figure 3. Contemporary art embraces replication, from Duchamp's L.H.O.O.Q. to Andy Warhol's consumer product prints. Reproduction itself is no longer seen as an infringement but as a means to critique, reveal, and supplement through the act of infringement.

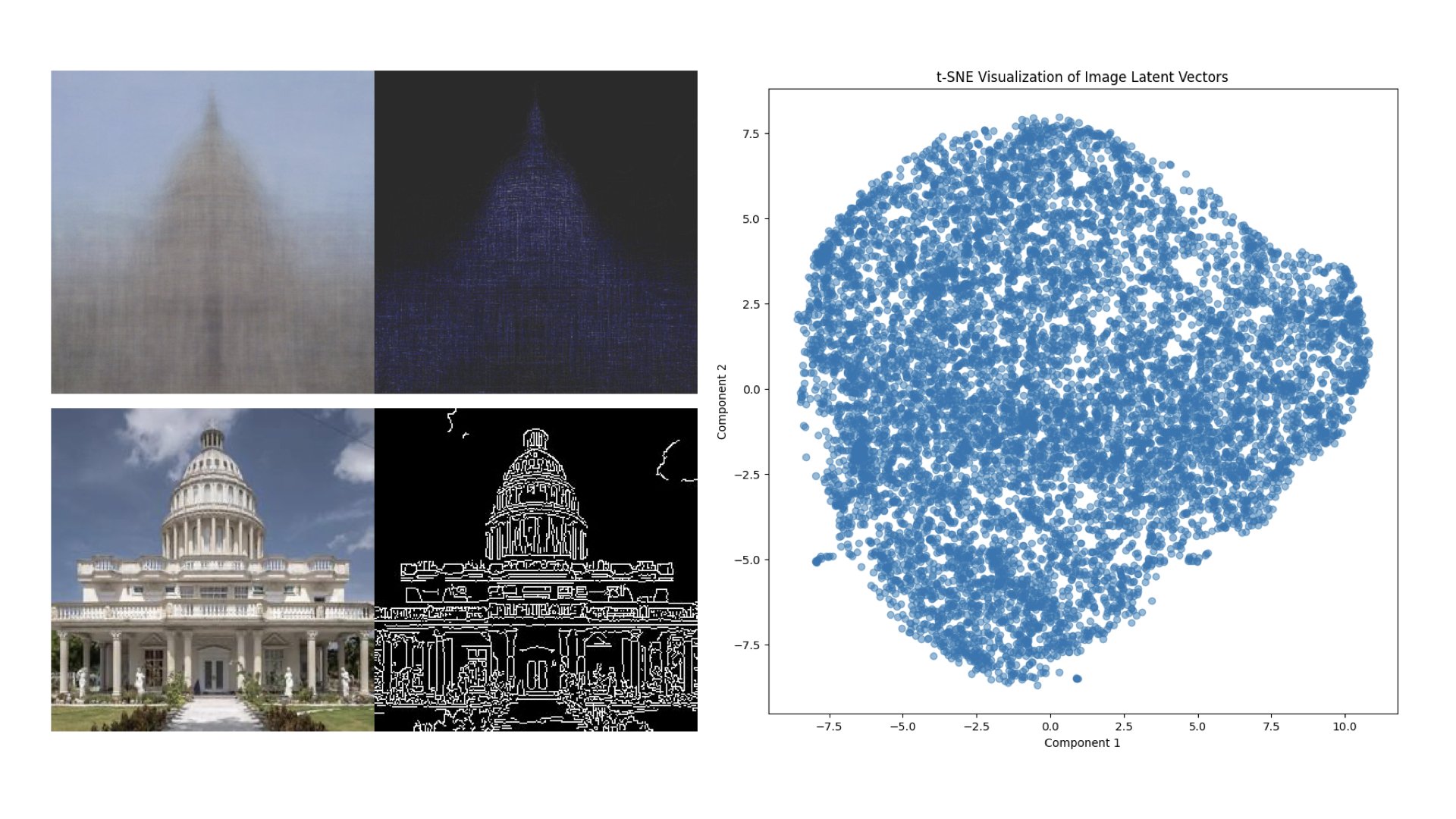

Figure 4. Located in Hengdian, the Ming and Qing Palace Garden is a full-scale replica of the Forbidden City that permits a range of activities impossible at the original site. This replica offers greater flexibility, serving as the filming location for numerous movies and television shows. As a result, the impressions most Chinese people have of the Forbidden City are largely shaped by this replica. Notably, ticket prices for the replica often surpass those of the actual Forbidden City.

Shanzhai as the Ship of Theseus

Originals are solidified and anti-change. Their foundation relies on the linear concept of time, which gives rise to the ideas of "first," "original," and "initial."The legitimacy of origin is established in the fixed state of its first appearance. The moment when the Mona Lisa was signed and framed, its status as an original was recorded. Any variation in brushstrokes, character outlines, or dye materials would be deemed counterfeit. Even if erosion renders the work unrecognizable, it necessitates restoration to its initial state. Also, the institution owning the Mona Lisa has to protect it through publication, making more people aware of and recognizing its genuine state. Owing to the uniqueness of the genuine, both the "record of the original state" and the "promotional materials" need to be a copy, official copies, and genuine replicas. Institutions negate "folk replicas" through "official replication" to preserve their interpretative authority over the original. Therefore, defining an original or genuine product hinges on preserving and promoting its fixed state. Preservation involves restorative efforts that continually return the product to its original condition, defying the effects of time. In contrast, promotion is a strategic effort to disseminate its original state, aiming for recognition and exclusivity. Ironically, the endeavor to protect the unique, inviolable original is achieved through replication.

Inherently, there exists a Ship of Theseus paradox: the original is constantly undermined by the forces of erosion, forgetting, decay, maintenance, care, and repair over linear time. So, is the Ship of Theseus still the original ship? Is the essence of the original material or conceptual? If the essence is material, do the ravages of time and subsequent repairs compromise its originality? In other words, how do we define the original when the material is in constant flux? Conversely, if the essence is conceptual, do replicas based on the original concept hold the same significance as the original? Plato elucidates that while specific things are fluid and ever-changing, their underlying ideas and concepts remain eternal; the concept of a horse does not pertain to any particular horse but instead encapsulates the essence of a horse. This notion parallels Joseph Kosuth's "One and Three Chairs," which interrogates the reality of the physical chair, the image of the chair, and the concept of the chair. Kosuth posits that the concept of the chair, as a signifier, encompasses the majority of chairs, including the two adjacent representations, thereby making it the most real chair. Therefore, when both the Shanzhai and the original share the same signifier, and even when the Shanzhai, as the image and concept of the original, removes some non-essential components, can it better represent the concept than the original itself? Neither the original nor any individual Shanzhai can fully represent the concept on their own; only when they appear collectively can certain key traits be highlighted, and the image that emerges is the ultimate original.

Figure 5. In the multitude of counterfeit Nike products, there are creative counterfeits: 'JUST BREAK IT,' 'Just did it.' These counterfeits are sold to consumers in third-tier cities and counties in China who are unable to purchase authentic Nike products. Most of these consumers do not mind whether their purchases are genuine. In fact, some consumers even prefer counterfeit products because they are priced lower and their quality is almost indistinguishable from authentic ones.

Figure 6 .Overlapped Development of The Shanzhai Nike and Adidas, two of the most famous sport brand in China. Image by author.

Shanzhai as Customization

“China's continuity has never been disrupted. The key ontological reason for this is that China is a civilization that employs 'becoming' (变在) as its methodology rather than adhering rigidly to the essence of 'being' (存在).”

— Zhao Tingyang, "China as Methodology"

The dichotomy between authenticity and imitation becomes blurred in a worldview of flux. Shanzhai and the original become objects that evolve into each other, mirroring the interchange of positions between the center and the periphery. The Chinese philosophy of impermanence and change leads to a less rigid attachment to fixed authenticity, favoring instead a flexible approach based on specific contexts. This approach, known as 道 (Tao) or the way of nature, underpins Chinese culture. It draws from the impermanence and rules of nature to form a philosophy that adapts to change, as expressed in the saying: 穷则变,变则通,通则久 (Impasse leads to change; change leads to solution; solution leads to development.).

Shanzhai, rather than being a mere replication or imitation, embodies a method and pattern of natural growth that responds to specific circumstances. This highly contextual form of Shanzhai, influenced by diverse environmental factors, exhibits remarkable vitality and creativity, often evolving into unexpected forms. It transcends simplistic reproduction or plagiarism, embracing a dynamic process of adaptation and innovation.

In natural evolution, all species evolve, diverge, and mutate. A species splits into two due to environmental mechanisms. The new species is not a Shanzhai of the original, nor are the divergent species Shanzhai of each other. They are not intentional clones but rather instances of natural regeneration, each responding to their respective environments and conditions. Despite potential similarities in appearance, function, and essence to previous generations, even their descendants cannot be defined as counterfeit Shanzhai.

Nature's pattern of extensive reproduction through small-scale mutations based on specific and feasible mechanisms is a response to complex environments. We cannot identify a specific individual as the original, nor can we determine which generation was the first. The emergence of new species, seemingly triggered by mutations, is an accumulative improvement arising from the evolution of the previous generation combined with environmental changes. This process unfolds through minute mutations during cell aging and division and in every subsequent generation of newborns.

In a nation embracing the concept of Becoming, there is no Shanzhai. China as a nation has undergone numerous variations, integrations, cultural iterations, and territorial reorganizations. Its essence has been redefined countless times, eschewing a rigid adherence to "sameness" in favor of adapting to changes based on 天时,地利,人和 (timing, location, and people), which has enabled its continuation to the present day. Contemporary China is a vastly different subject from China during the Zhou dynasty, yet there is a spirit of continuity. Criticism does not occupy a major position in China's methodology seeing that criticism is based on the essence/definition of an unchangeable doctrine. For China, there is no unchangeable entity, so its core methodology is inclusive. This includes the well-known modernization turn in modern China: Mao Zedong Thought—a Chinese-style Shanzhai Marxism and Chinese-style modernization, reform, and opening up, and the one country, two systems model. A socialist system with Chinese characteristics. “符合国情”(Fitting the national conditions) is the contemporary version of the Becoming methodology.

In ancient Chinese art, there is no Shanzhai. The appearance of authentic works changes, as they are stamped with new seals and inscribed with new poems by collectors throughout the ages, along with dimensions increases. The importance of a work can be gauged by the number of times it has been collected and subsequently altered. Often, the most famous works are those that have undergone the most modifications. The famous piece may have numerous copies, some of which are meticulously copied by skilled literati or even masters, becoming multiple replicas with equal effectiveness and value. The influence of a painting or calligraphy can also be gauged by the abundance of its replicas. Copies may even supplant lost originals. This pattern resembles the reproduction of species in nature to enhance their chances of survival; when a "leader" dies or loses ability, they are replaced by the capable, without affecting their legitimacy. In this context, while the "original" can be clearly identified, it does not diminish the fact that other copies, aside from the "authentic work," also possess their trajectories.

Shanzhai is a manifestation of Becoming. Shanzhai is a situational customization of the imitated object (essence) based on reality. They disrupt the uniformity of essence, challenge the colonialism of authenticity, and bridge the gap between ideas and tangible presence. In the seemingly irreconcilable opposition between replicability and contextualization, Shanzhai offers a unique solution. This form of imitation eliminates the original's non-essential value components and incorporates the specific local needs, resulting in more outstanding practical operability than direct replication.

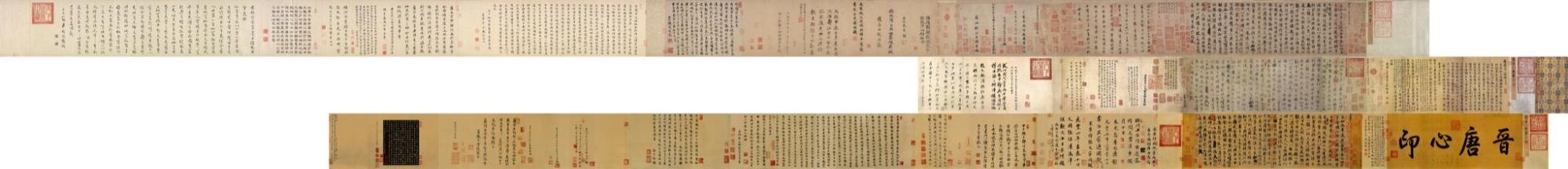

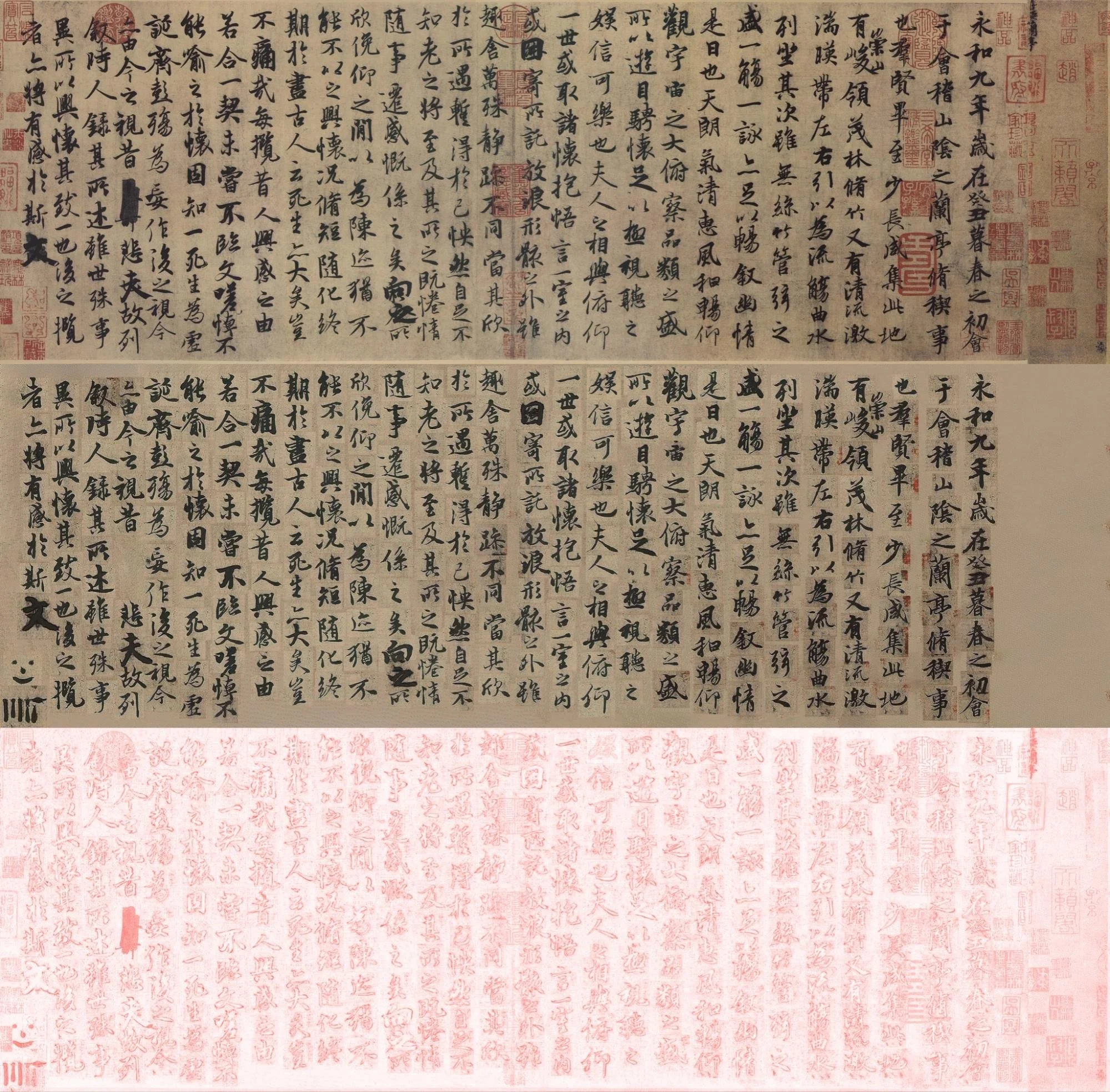

Figure 7. The renowned calligraphic masterpiece, Lanting Jixu, has been replicated by a multitude of individuals, including Yu Shinan, Chu Suiliang, Feng Chengsu, and Ouyang Xun, collectively referred to as Tang Dynasty copies. Among the extant reproductions, the Shenlong Copy stands out as the most celebrated and esteemed. The three primary surviving renditions featured in the figure are the Shenlong Copy, the Tianli Copy, and the Mifu Siti Copy. Although they are not the authentic, these copies are accorded equal reverence to genuine originals. Notably, the inscriptions and seals on each iteration bear distinct trajectories, resulting in variations in their dimensions and contents.

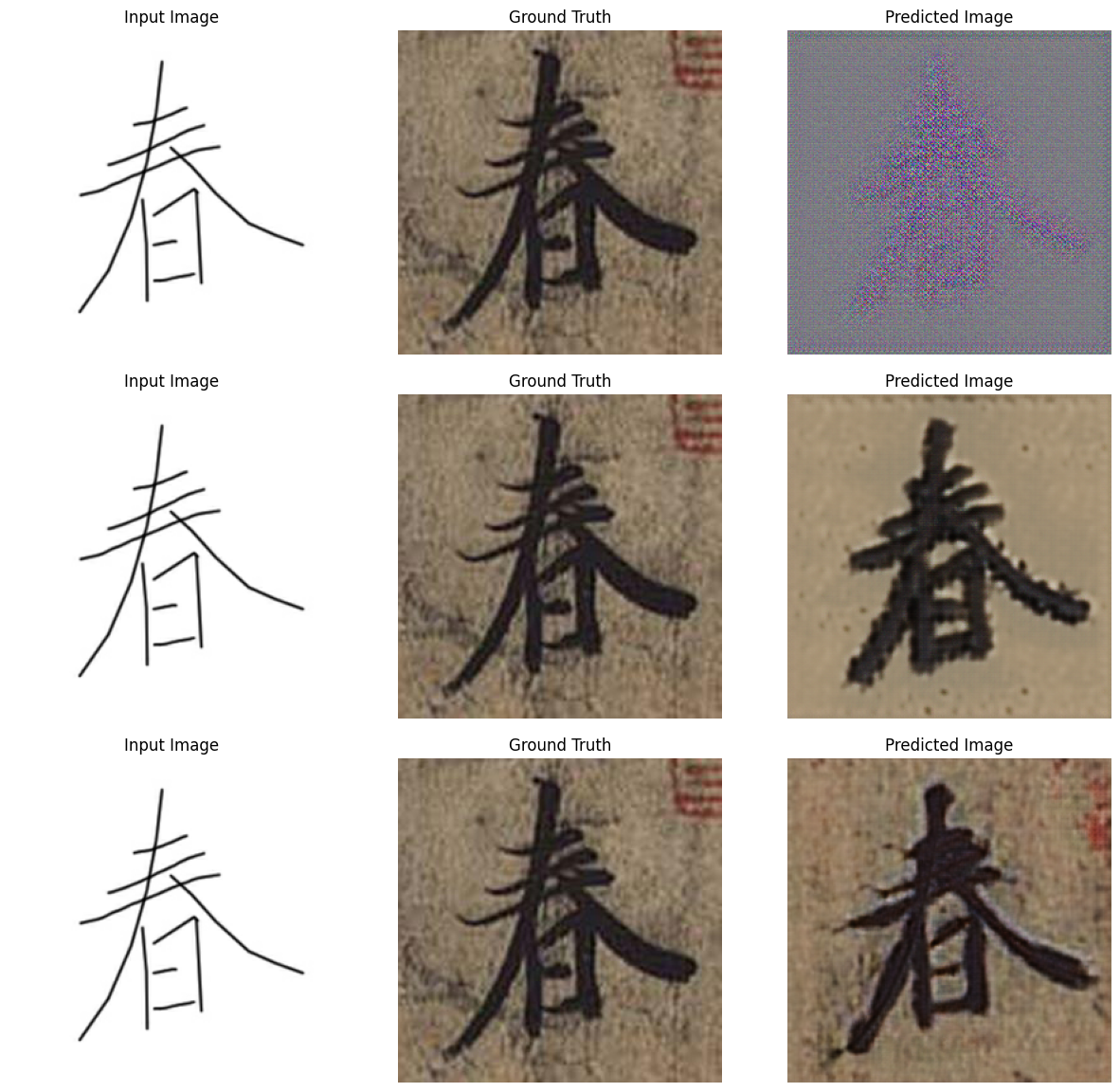

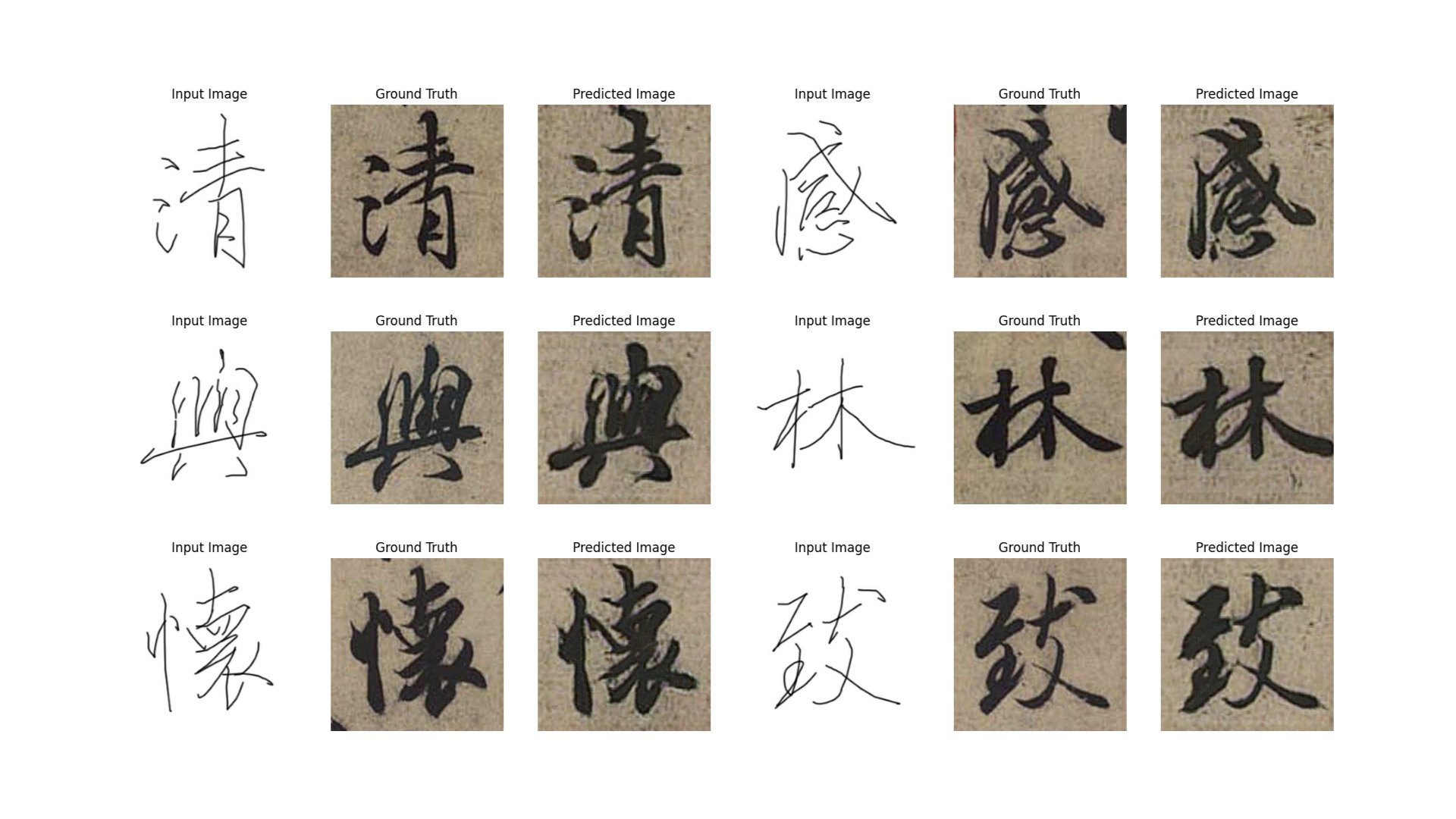

Figure 8. Top: The Shenlong Copy, Feng Chengsu, Tang Dynasty(widely regarded as the closest replica to the original, is currently housed in the Beijing Palace Museum);

Middle: The Pix2Pix Copy, Zhenghua Li, 2024, Trained on Machine Learning Model: Generative Adversarial Network(GAN); Image by author.

Bottom: Highlighted difference between two copies. Image by author.

Figure 9. Training process of the GAN model: Top: 0 passes, Middle: 4000 passes, Bottom: 40000 passes. Image by author.

Figure 10. Comparison between the original copy and predicted result after the model trained for 50000 passes. Image by author.

Figure 11. shows a Diagram of the neural networks showing different approaches for copying Lanting Jixu, which operates in pixels instead of brush strokes. Image by author.

Shanzhai as prothetic

In Chinese, a prosthetic limb is known as 假肢, yet it can also be called 义肢, meaning "justice limb." In this way, what is "fake" transforms into a form of "justice," embodying strength and virtue in its artifice. Shanzhai, as a form of imitation, can also function as a prosthetic for regions facing developmental disadvantages. These disadvantages arise from uneven regional development, where some areas advance first and set the standards, rules, and definitions of what is considered normal and universal. As a result, underdeveloped areas that do not meet these standards become metaphorically disabled. During economic, political, and cultural exchanges, the more developed, standardized regions often dominate or disregard the less developed ones.

While we often lament the homogenization brought about by modernity and globalization, it is crucial to focus on the "exceptional" areas that remain outside this process. These regions are excluded from what is considered normal. Although architects and planners might strive to break away from conventional norms, some regions cannot achieve these standards; for them, normalcy is a luxury. Everyday amenities we take for granted. Such as shops, elevators, transportation, roads, and clothing are luxuries in these underdeveloped areas. Consequently, as these areas are excluded from the standard, they remain perpetually disadvantaged and metaphorically disabled.

With technological advancement, solutions for physical disabilities have shifted. From covering and concealing to replacing and repairing, or even enhancing, leading to various prosthetics - artificial eyes, cochlear implants, artificial hearts. The goal of these artificial aids is to imitate and replace natural items, allowing an unhealthy body to function normally. For instance, for a healthy body, the essence of feet is the ability to stand, walk, and run, rather than the physical feet themselves, the material structure of the feet exists to realize their function. Prosthetics aim to restore function, standing, walking, running. Rather than the material itself, emphasizing the concept of the original over its material essence. In material production, the "fake" in Shanzhai is an "artificial" or "prosthetic" authenticity, enabling groups with material disabilities to have a state similar to normalcy.

A replica indicates authenticity not by origin but by its ability to evoke and embody the unattainable within a new context. Authenticity can emerge through context, intention, and emotional connections. The Eiffel Tower is "THE EIFFEL" because it symbolizes Paris; other replicas evoke a longing for the romanticism it brings to their cities. However, despite not being perfect imitations, these replicas generate sentimental value through their intention, making them contextually indistinguishable from the original.

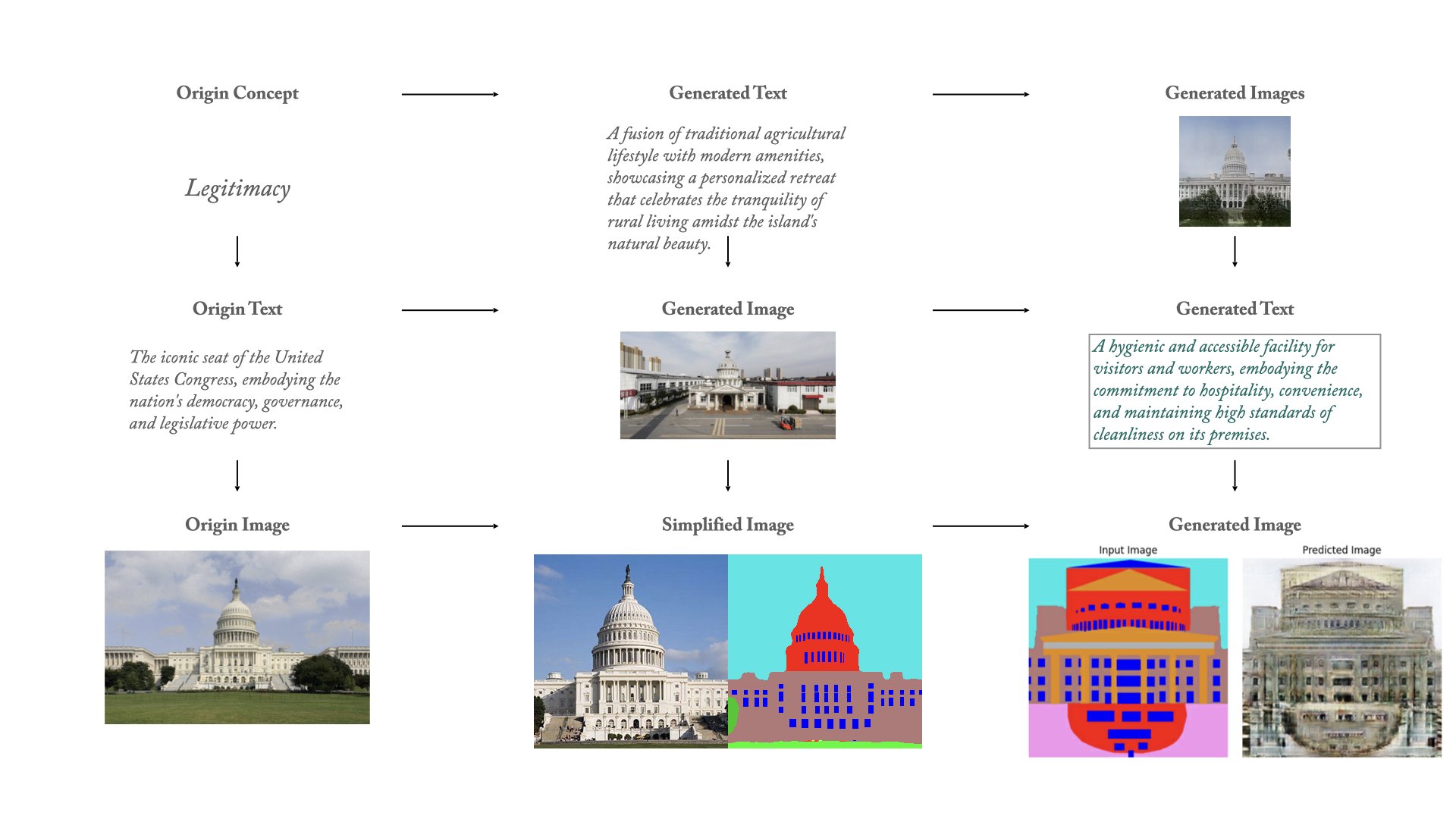

The act of replication democratizes access to items considered "luxurious," "unique," and "authentic." In China, numerous replicas of the U.S. Capitol building exist, each adapted to its context, used as government buildings, university libraries, hotels, theme park attractions, or private homes. Some are exact replicas, while others modify elements such as roofs, window sizes, and driveways. This design venture has morphed into its own genre, a form of reverse critical regionalism. Initially inspired by Roman and Greek architecture, the U.S. Capitol building was itself a replica embodying the nation's founding ideals. Chinese replicas reinterpret these aspirations, creating new architectural imaginations. While often mocked, they ironically embrace democratic ideals.

In the case of Chinatowns, replicas of Chinese architecture serve as protection for the immigrants living there. Chinese Americans have historically had a complex relationship with the United States. In the late 19th century, San Francisco Chinatown hired White American architects to create more oriental architecture, transforming the neighborhood into a theme park-like area. This approach, while further isolating and marginalizing the community, was necessary to ensure its survival. The architectural style combined aesthetics from various parts of Asia, forming a manufactured culture that, over time, became authentic to Chinese Americans—a good copy.

Indeed, numerous similar examples can be found. With immigration, racial and economic shifts, and urban-rural integration, Shanzhai may serve as a universal method for bridging regional disparities, a form of original replication that aims not at cloning but at regeneration.

Figure 12. Overlapped Development of The Shanzhai Eiffel Tower. Image by author.

Figure 13. Overlapped Development of The Chinatown Gates. Image by author.

Figure 14. A Dataset of the spectrum of Neo-classical Dome structure and Shanzhai US Capitol in China.

Figure 15. With the help of the convolutional neural network (CNN), the dataset was decoded into a 128 dimensional vector.This digitized itself is a form of Shanzhai. Image on the right is the t-SNE Visualization of the Image Latent Vectors. Image by author.

Figure 16. Generated new Shanzhai with the trained data.

Shanzhai as cyborg

A cyborg represents a reverse mimicry of the original, aiming not to approach but to surpass it. The cyborg worldview also rejects the notion of Being, opposing the idea of fixed wholeness as the essence of individuality. Instead, it embraces Becoming, which transforms individuals, broadening the definitions of "human" and "normal." This perspective acknowledges the legitimacy of partial "non-human" and "fake" substitutes coexisting with the human body. In this context, prosthetics are not necessarily for "repair" but rather for "enhancement," subsequently not only bridging the gap between disability and normality but also elevating both to a higher state. A cyborg is a proactive Shanzhai, actively abandoning authenticity in pursuit of an idealized fakeness. The cyborg's prosthetic is not a replica of the original but rather a design from the original that denies the present reality and attempts to mimic an imagined perfect future.

Shanzhai as a Virtual Reality

Reality is so complex that any of its descriptions is inherently an untrue statement. Human beings may need and excel at imitation. The complexity of reality surpasses the human senses, necessitating simplification, which entails retention and elimination, subjective filtering. Thus, all human senses are inauthentic representations/imitations, or we might say that reality is so complex that any narrative constitutes a virtual reality, a (political) assertion. True is incomprehensible, whereas actuality is a subjectively understandable truth is actuality a representation of True, so is it also a Shanzhai?

Reproduction begins with the necessity of memory; as an object or event holds value in being reproduced, it requires remembrance/recording to allow for repetitive viewing. Whether concerning the quantity of an object, the history of a specific period, or the manufacturing process of something, these are all forms of recording, storing, and retrieving the essence of the thing itself—images. If part of the reason for recording is to simplify reality, then the original need for recording is the scarcity of the original, both spatial and temporal. The irreplaceable nature of a historical event over time requires its documentation, allowing for future glimpses of the scene, thereby rendering the image of the event functionally equivalent. Similarly, the uniqueness of an artwork, such as Van Gogh's Starry Night, necessitates its documentation for distribution and study. Therefore, for a child in a village in China, the printed Starry Night in their art textbook is tantamount to the original displayed on the walls of MoMA (the Chinese Van Gogh).

Is an image a form of Shanzhai? Is the Starry Night found on the Internet a form of Shanzhai? Is a photograph of an architect's building, stored on a hard drive or the Internet, or displayed through a screen or projector in a class presentation, a form of Shanzhai? Shanzhai is the reproduction of the True; Shanzhai is reality.

How can we understand Shanzhai?

Shanzhai represents the resistance of grassroots and marginal cultures against official culture.

Shanzhai is the freedom of sharing, replicability, and material reproduction.

Shanzhai is the genetic mutation of natural evolution, an iterative regeneration.

Shanzhai is the mirror image of concepts, the shared value of originals.

Shanzhai follows the natural way, adapting to local conditions and national circumstances.

Shanzhai is the realization, localization, and concretization of concepts.

Shanzhai is the repair of disability, an equivalent substitute.

Shanzhai is the stitching of imbalanced regions, a regenerated reality.

Shanzhai is the imitation that transcends the status quo, a counterfeit utopia.

Shanzhai is ubiquitous imagery, a reproduction of reality.

Shanzhai is a device for social equity.

Figure 17. Machine Learning Models provide different trajectory for tokenizing images, text, and meanings. Image by author.

Figure 18. Comparison between the original copy and predicted result. Image by author.

Figure 19. Overlapped Development of The Chinese White House. Image by author.

Figure 20. is a generated image from a empty image, showing the hidden information of the trained data, and how the trained model understand the essence of the image of the dataset, the core of Shanzhai. Image by author.

Figure 21. A new generated Shanzhai from the trained model. Image by author.

Figure 22. Chinese Van Gogh, Photo: Yu Haibo.

A Blank Canvas

In the tapestry of our globalized world, Shanzhai weaves a delicate thread, challenging rigid notions of authenticity and originality. It is not merely an echo, but a reimagining a song in a different key. Transcending imitation, it becomes a dance of resilience, blossoming in the shadows of progress and relentless circulation. Idleness, once scorned as laziness and waste, finds redemption through Shanzhai. Victorian values and modern systems cast idleness as a vice, but Shanzhai transforms it into a fertile pause, a breath held before dawn, inviting reflection, adaptation, and quiet creativity.

In art and architecture, idleness is the serene stillness of a pavilion or the labyrinthine corridors of a mall, sanctuaries resisting perpetual motion. Here, the spirit of Shanzhai thrives, turning the mundane into the miraculous and the overlooked into the indispensable. Shanzhai reclaims idleness, not as inactivity but as strategic stillness, a pause that recalibrates the heart, allows the mind to wander, and reconnects the soul to its roots. In these moments, true innovation sparks, tapping deep wells of cultural memory and identity.

As we grapple with relentless activity and the need for rest, Shanzhai offers a new lens. It asks us to see idleness as a crucible of creativity and resilience. By transforming perceived emptiness into spaces of opportunity, Shanzhai democratizes creation, enabling everyone to produce or obtain their own 'good copy.' Shanzhai bridges chasms between regions, past and future, genuine and replicas. It enriches our cultural fabric with tradition and innovation, reminding us that pervasive truths are often found in the quiet, the idle, the unexpected places.

Bibliography:

Blackburn, Simon. The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

Boys, Jos. "Cripping Spaces? On Dis/abling Phenomenology: In Architecture." Log, no. 42, Disorienting Phenomenology (Winter/Spring 2018): 55-66. Anyone Corporation. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44840728.

Han, Byung-Chul. Shanzhai: Deconstruction of Chinese. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2017.

Han, Tao. "Images on Modernity: Examples, Discourses and Architecture." Design Community 2021, no. 01: 69-77.

Institute of Linguistics, Chinese Academy of Social Science. Contemporary Chinese Dictionary. Beijing: The Commercial Press, year.

Lodermeyer, Peter. Personal Structures: Time, Space, Existence. No. 1. Cologne: DuMont, 2009.

May, John. "Everything is Already an Image." Log, no. 40 (Spring/Summer 2017): 9-26.

Sha, Yuwei. "Shanzhai, a New Term for Knock-off." China Terminology. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1673-8578.2008.06.022.

The Book of Changes, Treatise on the Appended Remarks Part II, 《易经·系辞下传》, The Seventh Section of Chapter Fourteen, Zhou Dynasty, http://keywords.china.org.cn/2022-10/13/content_78463699.html.

Zhao, Tingyang. "China as Methodology." Journal of Shaanxi Normal University (Philosophy and Social Sciences Edition), no. 2 (2016).

He, Yanzhi. Lanting Shimo Ji 《兰亭始末记》. Tang Dynasty.

Zaera-Polo, Alejandro. "Cheapness: No Frills and Bare Life." Log, no. 18 (Winter 2010): 15-27.

Li Zhenghua is a Master of Architecture candidate (Class of ’26) at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s School of Architecture and Planning. He received his undergraduate degree from the Central Academy of Fine Arts in China and previously worked for six years as a Project Architect at the People’s Architecture Office (PAO), contributing to projects ranging from public infrastructure to primary schools. His professional work spans the full design and construction process, with a strong emphasis on social responsibility and equity in architectural practice.

His current research focuses on cheapness as a critical driver of social equity in architecture, examining its relationship to modernization, production, and aesthetics, particularly within China’s unfinished modern condition. Through architectural design, visual art, and fashion, he explores modularity, replication, and algorithmic processes. He co-founded the sustainable clothing brand Re-Ex-De-Of- in 2021 and established QU@$! Studio in 2022 as a platform for applied research on cheapness.

Cheng Qin is an interdisciplinary sculptor based in Cambridge, MA, with a background in architectural design, sculpture, and digital fabrication. His practice centers on creating actant instruments—inanimate artifacts or machines that autonomously perform and embody narratives of resilience. By pushing these artifacts beyond their static nature, his work explores fleeting, affective moments that exist between memory and speculation.

With professional experience as a design consultant for artist Sarah Oppenheimer and a designer for Olafur Eliasson, Cheung brings technical abilities to speculative design thinking. He was an artist in residence at Aalto Residency in Finland and at the Monopol School of Sculpture Berlin. His work has been exhibited internationally at institutions, including the Willem de Kooning Academie(Rotterdam), Yale’s SOA North Gallery, BCA Gallery(Shanghai), Dutch Design Week 2024, and MIT’s Wiesner Art Gallery.