Material and Method

by Varun Maniar

Varun Maniar / is a candidate in the SMArchS Architectural Design (AD) program at MIT. He holds a Bachelor of Architecture from Cal Poly San Luis Obispo. His research focuses on bridging the gap between those who design and those who fabricate our buildings, exploring how knowledge of material, process, and construction can inform architectural practice. Prior to MIT, he worked for three years in high-end architectural metal fabrication.

My first semester at MIT Architecture has been shaped by an ongoing negotiation between discursive analysis and material prototyping. Much of my academic program operates in the realm of speculation, theory, and representation. Meanwhile, my background is rooted in metal fabrication, where knowledge is accumulated slowly through repetition, attention, and failure under the guidance of master craftsmen. The images collected here came from that process: work produced by students in a weekly welding session, and fragments from a set of furniture pieces I am developing over the next year.

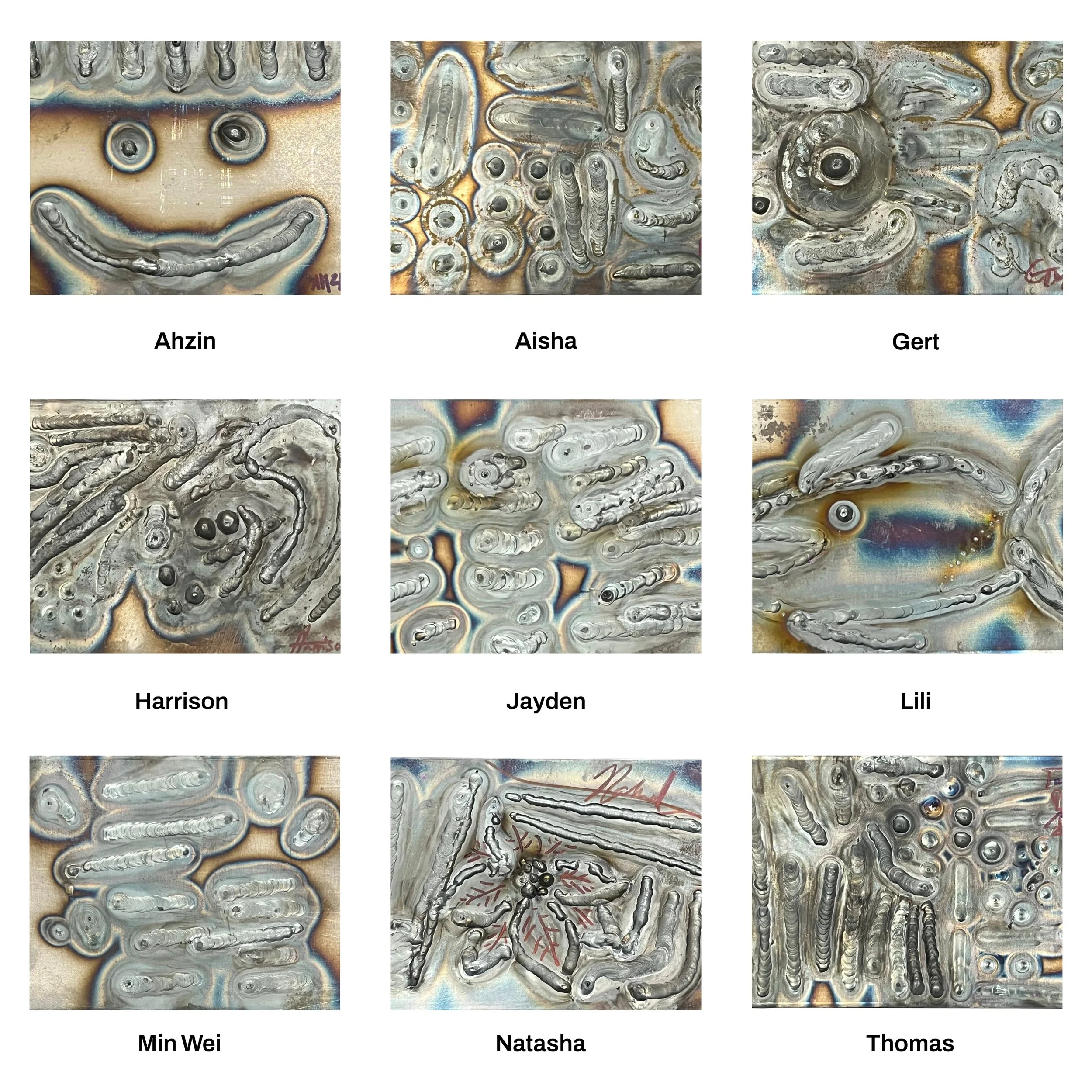

I taught a short weekly Tungsten Inert Gas (TIG) welding class in the Metropolis shop. Many students arrived curious but were unsure of how the welding process worked. TIG welding uses a torch to create a focused electrical arc to melt metal, while a separate hand feeds in filler material. It is slow, precise, and particularly unforgiving — very different from the fast and forceful welding people often imagine.

The class moved through a sequence of basic skills on a small steel plate: First creating a molten “puddle,” then adding a tiny amount of filler to make a tack, and finally attempting to guide the molten metal in a straight line. These motions are simple in theory but surprisingly challenging in practice. Everything depended on steadiness, timing, and control.

Figure 1: Students working on their welding canvases

TIG welding is not something anyone can learn in two hours. The brief session only gives a sense of the material, motions, and the attention demanded by the welding process. Students often expect to produce a clean, continuous line on the first try. Instead they are met with the material’s resistance: The torch drifts, the puddle recedes, a ‘cold’ tack refuses to hold. In these moments, the challenge is not failure, but an encounter with the skill, patience, and embodied knowledge required to weld well. Most will not weld again. Ultimately, the exercise only provides a brief preview of the labor and expertise that brings buildings into their physical forms.

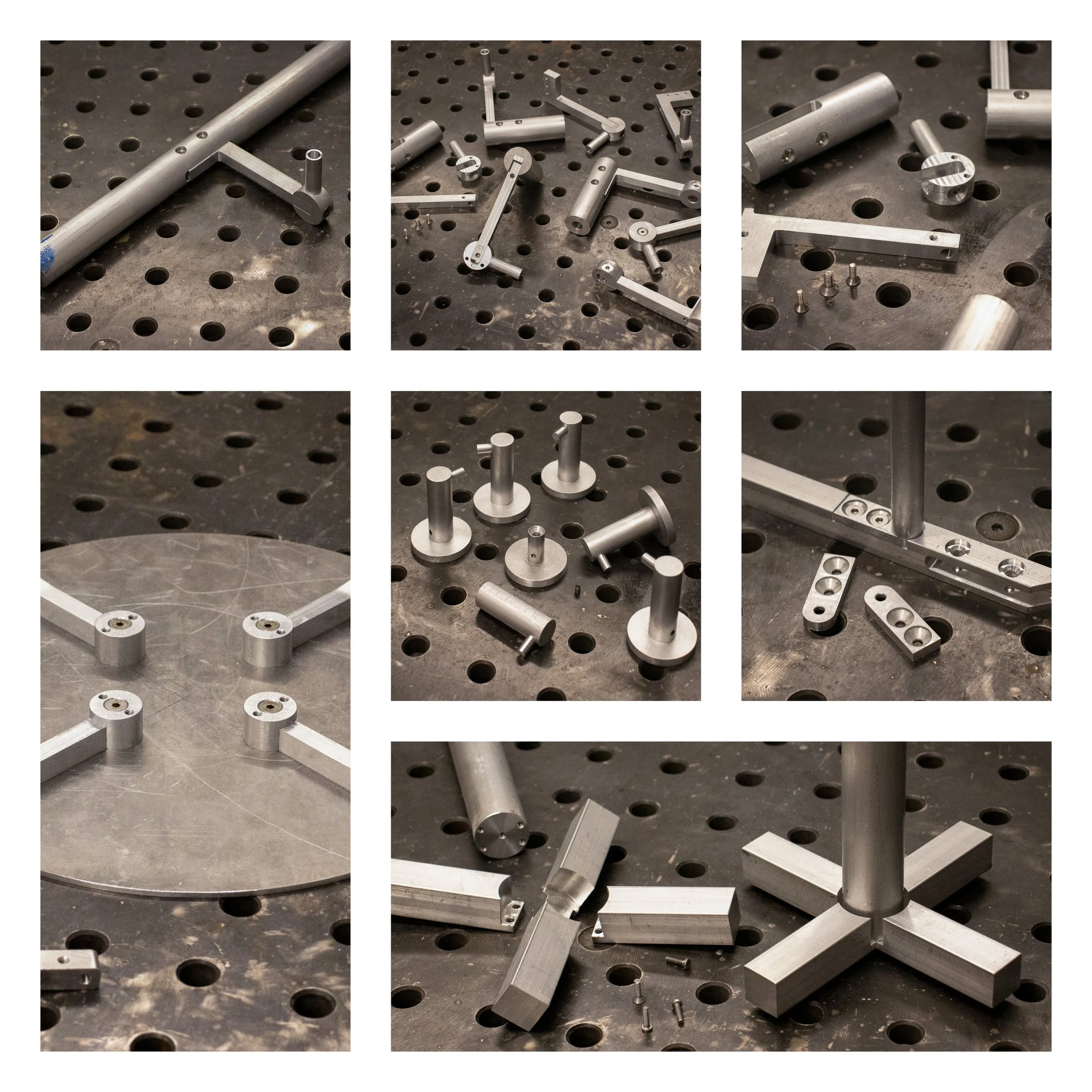

In parallel to my teaching, I have been developing a series of flat-pack furniture pieces. These are not part of my formal research work but act as a counterbalance to the fast pace of lectures and seminars in school. The series explores modularity and longevity. Parts are designed to be disassembled, transported, or repaired over time. Spending time in the shop is essential for keeping my craft alive. At MIT, and within most courses, making is rarely treated as a rigorous academic endeavor. Classes that involve physical production often prioritize concept over process or the quality of the final object, leaving little space to develop expertise.

The equipment at MIT is different from the precision environment of professional shops I have worked in. Welding stations are modest and machines drift out of calibration. As a result, I have adapted many of my designs for using CNC-milled aluminum parts with mechanical connections, aligning with the equipment available with more ease.

Figure 2: CNC aluminum furniture parts produced by author

This has created two distinct kinds of fabrication workflow days. CNC demands vigilance and focus. The machine itself has no intelligence: it moves extremely quickly (even at 25% rapid traverse speed) and cannot anticipate collisions or correct a misaligned cut. As it runs, I lean over the enclosure, watching through the acrylic panel as coolant sprays and rebounds off the cutting tool, obscuring the view, with one hand hovering over the emergency stop button in case something goes wrong. These hours are mentally taxing — a controlled anxiety that keeps every movement intentional. Other days are spent shaping material by hand. Filing, deburring, and finishing are physically exhausting but deeply satisfying. Although these days are less frequent, they remind me why I value craft.

Working alongside engineers in the maker-spaces has expanded my understanding of tolerance, precision, and machining strategy. Most of the parts I make are accurate to 1/64”, common for high-end metalwork but unacceptable in some engineering contexts. In the Deep, a machine shop in Building 37, I have learned to read an analog caliper, use pin gauges, and work with telescoping gauges — small but essential tools for verifying dimensions and achieving slop-free sliding or intentionally tight press fits. The number of zeros in one ‘thou’ (0.001”) is even starting to come to me easier. These technical skills continue to guide the direction of my furniture work and shape how digital parts meet the world through surface, joinery, and touch.

Being a crafts person in today’s world carries a strange freedom. In a capitalist economy, productive labor rarely cultivate artisans; the work is often systemically deskilled, broken into repeatable tasks to reduce the reliance on individual expertise. Yet I deliberately cultivate these skills, combining them with design thinking and digital fabrication in ways that resist that logic. There is a certain empowerment in working with care and attention in a culture that prizes speed and efficiency. Craft is not just a way of making objects, it is a framework for thinking and inhabiting a world that too often moves too fast.

Metal shops across campus are often quieter than the spaces dedicated to wood or digital tools. I would like to see more architecture students working with metal, not to master it, but to experience another way of thinking through material. Anyone who is curious or wants to explore a project is welcome to ask. A drawing is helpful; the rest can be figured out together.