No Sweat Architecture: Manufacturing Cool

by Ahzin Nam

Ahzin Nam / SMArchS AD 27’ / Ahzin Nam is a designer based in Cambridge. She was a recipient of IDC Foundation Innovation Fellowship, the William Cooper Mack Thesis Fellowship, the Dinae Lewis Memorial Travel fellowhsip, Benjamin Menschel Fellowhship, and Snarchitecture Commencement Prize.

She has worked as an architectural deisgner at Food Architects and participated in renovating the the communal space of Creative Time, a glowing merch booth for a music festival in NYC, community lighting project with Brownsville Justice Center, and various installation projects for minority owned fashion brands.

She holds BArch degree from Cooper Union, and her work has been featured in E-flux, Tallinn Architecture Biennial, and NYC x Design. She is currently in SMArchs AD program at MIT.

The Birth of Coolness: Making Everyday a Good Day

Figure 1: The Story of Manufactured Weather, by the Mechanical Weather Man

“Permit me to introduce myself. I am the Mechanical Weather Man, – and I Manufacture Weather to order. The Boss says I’m a figment of the imagination – that an artist made me by endowing a control valve, or some such thing, with a pair of legs, a pair of arms, and a smile. But I like to think that I’m the visualization of an idea, - the Idea of manufacturing weather, to make ‘Every day a good day.’ […]

Two men, named Carrier and Lyle, had an idea about making weather mechanically, and today their apparatus is manufacturing more than four hundred million pounds of made-to-order weather every working day. […]”

Carrier and Lyle said, ‘Some days Nature makes perfect. Some days are good days, everything just right to make everybody feel full of life and to make it possible for these vigorous people to produce the things which contribute to our health and happiness. If Nature can make a good day once in a while we’ll manufacture weather and make ‘Everyday a good day.’”

The Story of Manufactured Weather, by the Mechanical Weather Man, Carrier Engineering Corporation, 1919.

Until mechanical cooling, “coolness” was tied to location and time. In the South, porches were a common architectural element where the residents cooled themselves with the natural wind and shades until the interior cooled down at night. The cultural practices of siestas during the hottest time of the day and summer trips to cooler regions emerged to bring people to find coolness.

The desire to detach coolness from fixed points is not modern. The privilege of escaping the heat, or the superimposition of coolness, was often reserved for the sacred spaces of power and healing. The Roman, Greek, and Persian civilization with hot arid climates[1], used evaporative techniques through pots, water pipes, and water absorbing walls. Active cooling, using mechanical parts, emerged from the 1840s, with physician and inventor John Gorrie of Florida who proposed the idea of cooling cities to relieve residents of "the evils of high temperatures." Pointing to cooling as the solution to prevention of illness such as malaria and faster healing, Gorrie patented a compressor powered by a horse, water, and wind-driven sails or steam in 1851. In 1889, Alfred R. Wolff designed a ventilation system for Carnegie Hall that used blocks of ice and steam-powered blowers to cool its wealthy patrons.[2] Ten years later, continuing cooling in the context of hospitals, the previous ventilation system was adopted as a cooling and de-humidification system at the dissecting room of Cornell Medical College to prevent cadavers from rotting. The refrigeration unit circulated brine solution through pipes, over which air was blown to cool the fifth-floor lab.

The technological breakthrough for mechanical cooling - or the birth of modern air conditioning - happened through technology described in the patent, "Method of Humidifying Air and Controlling the Humidity and Temperature Thereof" in 1914 by William Carrier that followed his patent for "Apparatus for Treating Air,"[3] from 1906, which demonstrated a spray-type mechanical system that focused on removing impurities from the air in commercial spaces. The 1914 patent describes a system based on Carrier's discovery that "constant dew-point depression provided practically constant relative humidity." Carrier’s method involved cooling air by passing it through a coil chilled by refrigerant, causing moisture in the air to condense and reduce humidity. By adjusting the airflow over the coils and regulating the refrigerant, Carrier could achieve a desired balance of humidity and temperature, which he claimed was essential for improving indoor air quality and maintaining environmental control in various settings.[4]

Initially applied to textile mills for "humidifying and regulating the humidity and temperature of air" (while also suggesting "general" applications), the patent was based on the humidity control system Carrier first developed for a publishing plant in Brooklyn. The plant, located on Metropolitan Avenue in East Williamsburg, was built for a humor magazine company, Judge, which produced four-color illustrations. Each color was printed in separate rounds, sometimes hours or days apart, exposing the thin paper to the humid summer air of the Northeast. The paper expanded, creating misalignments in the images during the multi-round printing process. Due to the industry's weekly release schedule, the humidity-induced delays became urgent, directly impacting the medium's reliance on consistent production. Around the same time, Willis Carrier, a 25-year-old junior engineer at Buffalo Forge Company (then best known for its pumps), was assigned Judge case as his first project. By 1902, Carrier had developed a solution involving fans, ducts, heaters, and perforated pipes, installed on the building's second floor. Cool water pumped from a well between the two buildings flowed through pipes inside the plant. In 1903, Carrier proposed adding a refrigerating machine to accelerate cooling. The technological success at Judge, where occupants gained the ability to control humidity, temperature, air circulation, and ventilation, marked the beginning of a new layer of control over indoor environments. The process was soon adopted by flour mills and Gillette, where humidity affected product quality.[5]

[1] Kheirabadi, Masoud. Iranian Cities: Formation and Development. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1991. 36. ISBN 978-0-292-72468-6.

[2] Steemers, Koen, and Simos Yannas, eds. Architecture, City, Environment. Cambridge Programme for Industry, Martin Centre for Architectural and Urban Studies. London: James and James, 2000.

[3] Buffalo Forge Co. Apparatus for Treating Air. US Patent 808,897, filed September 16, 1904, and issued January 2, 1906

[4] Buffalo Forge Co. Method of Humidifying Air and Controlling the Humidity and Temperature Thereof. US Patent 1,085,971, filed December 1, 1907, and issued February 3, 1913

[5] Barron, James. “Before Anyone Complained About the Air-Conditioning, an Idea.” New York Times, 2012.

Carrier’s invention made coolness an infinite condition, unbound by geographical coordinates or time and achievable through the manipulation of invisible elements via formulas. In the context of the history of mechanical cooling of the indoor environment, Carrier’s air-cooling system was the first superimposition of “coolness” on spaces of production. It was the first incident where the human subjects of previous climate imposing machines were replaced with other machines.

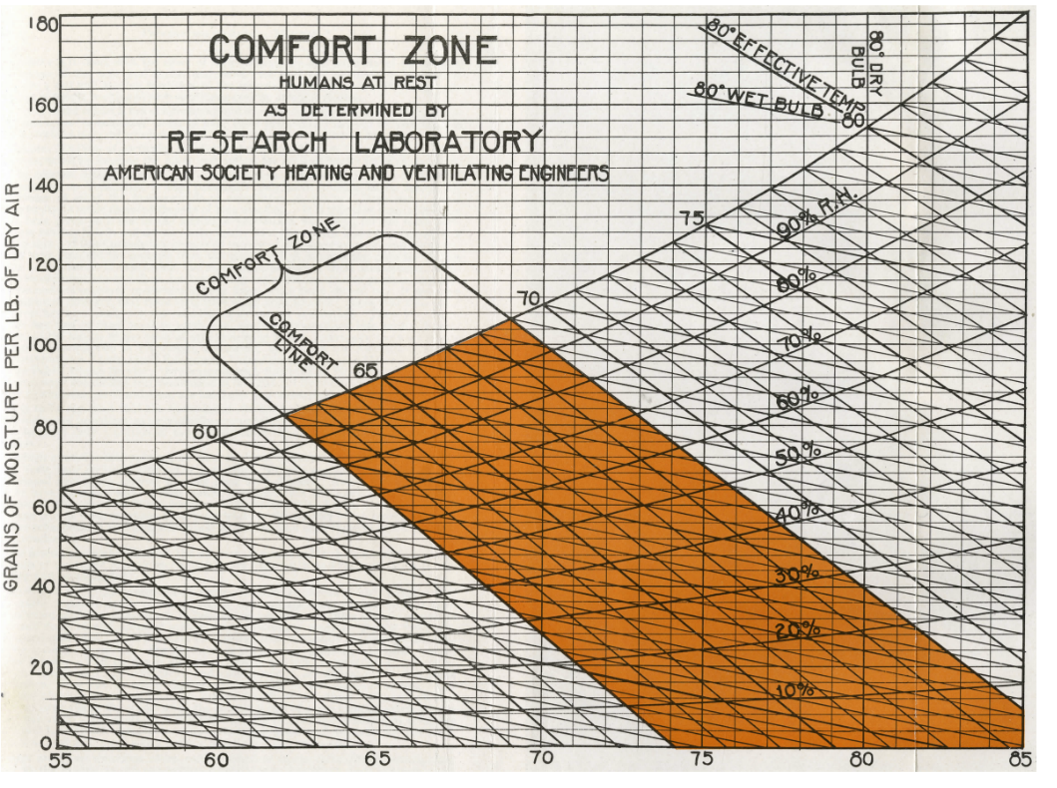

Despite the long history of evaporative cooling, one of the significant forces behind Carrier’s reputation as “the father of modern air conditioning” and the canonical status of 1914 patent can be attributed to Carrier’s other intentional and unintentional inventions between the submission and the approval of the patent: psychrometric chart and the comfort zone. Carrier used the principles of thermodynamics and psychometrics (the study of the properties of air and water vapor mixtures) to create the "Rational Psychrometric Formulae” that allowed engineers to calculate how air conditions could be manipulated to achieve desired humidity levels and temperature.[1] The initial intention of the chart was “the development of rational formulae for the solution of all problems pertaining to the phenomena of atmospheric moisture as related to psychrometry and to air conditioning” in context of “the application of [air conditioning] to many varied industries” that had demonstrated to be “of greatest economic importance.”

As scientists and engineers developed the ability to accurately map and calculate the thermodynamic behavior of water exposed to a dry atmosphere through constant enthalpy lines, the application of the concept to humans began to gain traction. The ideas of humans as biological heat engines, proposed by Lavoisier in the late 18th century, and engines must dissipate heat, popularized by Carnot’s cycle, led to the belief of thermal comfort could be understood as an equilibrium between human body’s heat gain and the environment’s heat loss.[2]

Psychrometric chart catalyzed the creation of “thermal comfort” as an engineering topic and reinforced the human body to machine metaphor. Using the terminologies and structures of psychometric charts, “thermometric” charts with “comfort zone” emerged. The idea of comfort became collapsed into two x and y axis of temperature and absolute humidity, while the curvature of dew point demarcated the limit where the invisible world of vapors turned into tangible water, inducing the state of change that becomes the main method of controlling “comfort.”

[1] Carrier, W. H.Rational Psychrometric Formulae: Their Relation to the Problems of Meteorology and of Air Conditioning Trans. ASME ASME. January 1911 33 1005–1039

[2] Teitelbaum, Eric, Clayton Miller, and Forrest Meggers. 2023. "Highway to the Comfort Zone: History of the Psychrometric Chart" Buildings 13, no. 3: 797.

[3] Life. Vol. 16, no. 4 (January 24, 1944): 104 pages. ISSN 0024-3019.

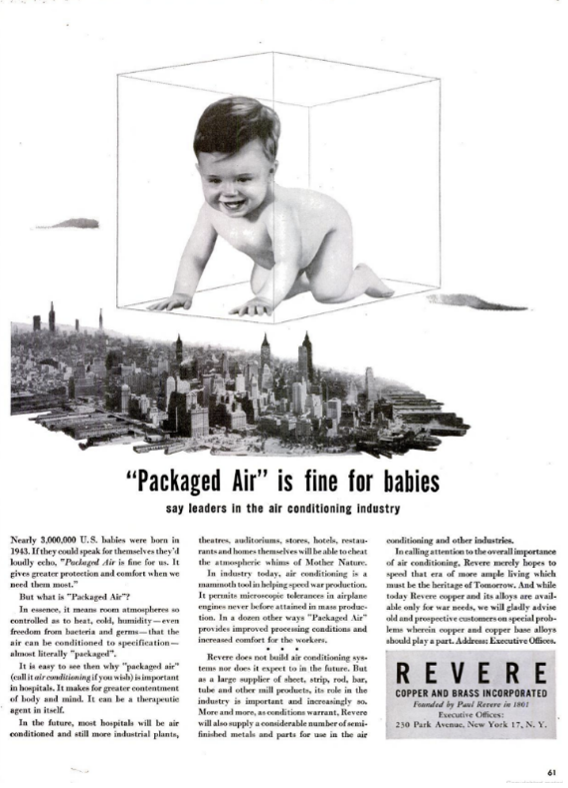

Carrier’s mechanization of human’s state of comfort was first implemented in 1906 through summer operation of theaters at Madison Square Garden. With no windows and heat generated by tightly packed bodies and light sources, the theater was a space that was impossible to inhabit in the summer. The previous attempts of cooling the space through tons of ice failed by the polluted lake water generating malodors. Using the uninhabitable space as a testing ground, Carrier’s new human comfort generating machine generated a spectacle with a large audience inhabiting previously avoided time and space. The conceptual infinity of coolness trickled down from the large spaces that sold coolness as a commodity from the 1930s to the everyday necessity. By the 1940s, the “luxury” became utility. The 1944 copy of Life Magazine celebrated the technological feat to “cheat the atmospheric whims of Mother Nature to its readership.[3] The Story of Manufactured Weather, by the Mechanical Weather Man, published by Carrier Engineering Corporation, Carrier promised “Everyday a Good Day,” on the footnote of every page.

Figure 3: “Packaged Air is fine for babies”

The transformation of Carrier’s technological invention of air conditioning adopted aspects of cultural inventions with an extra patent on the Psychrometric chart became the basis of climatic regulations for manufacturing comfort. The two axes of the chart conflated air conditioning with comfort and created a new definition of comfort. Any individual could define their current state on the chart from any point on the earth, and with the aid of mechanical systems, they could achieve comfort. The psychrometric chart led to developments in thermal comfort research and “graphic dissemination” throughout the 20th century. In 1963, Victor Olgyay published a book, Design with Climate that covered representative climate scenarios around the United States and included charts that used the psychrometric axes as a basis. Oglay’s chart and Givoni’s bioclimatic chart in 1976 demonstrated how the uniform “comfort,” could be achieved in different regional climate conditions.

In the 1960s, Olgyay’s thermal comfort research became integrated into ASHRAE 55 (Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy)[1] as a standard that established acceptable indoor environmental conditions for human comfort. Still confined by the grids of Carrier’s Psychrometric chart and comfort zone, American indoors are required to achieve the universal comfort using mechanically controlled indoor air, with minute variations based on metabolic rate, clothing insulation, radiant temperature, and air speed.

[1] Teitelbaum, Eric, Clayton Miller, and Forrest Meggers. 2023. "Highway to the Comfort Zone: History of the Psychrometric Chart" Buildings 13, no. 3: 797.

[2] Jean Baudrillard, "The Ecstasy of Communication," in The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, ed. Hal Foster (Port Townsend, WA: Bay Press, 1983), 128.

[3] Jean Baudrillard, "The Ecstasy of Communication," 128.

[4] Fredirc Jameson. Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham: Duke University Press, 1991.

[5] Jameson, Postmodernism, 83.

[6] Jean Baudrillard, "The Ecstasy of Communication," 128.

[7] Michael Osman, "The Thermostatic Interior and Household Management," in Modernism's Visible Hand: Architecture and Regulation in America (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018), p.3

The conflation of comfort with coolness that can be achieved anytime through manipulations of elements, Baudrillard describes a new mode of interaction of bodies and technology where direct relationship with objects are replaced with environmental system - “regulation, well-tempered functionality, solidarity among all the elements of the same system, control and global management of an ensemble.” The environment is “maintained” to control the interactions among elements that “continually communicate” and “stay in contact.” Each element is a piece of a network that is in the respective condition of the others where “opacity, resistance or the secrecy of a single term can lead to catastrophe.”[2] The amount of water molecules in the air is now understood to be directly entangled with the comfort level of the occupant. Such regulation of the body is then measured through additional apparatus, such as thermometer, allowing the management and external regulation of the occupants’ body. Through outsourcing of the self-regulation system of a body through sweat to electrically powered air conditioners, “the real” becomes “satellized,” the concept which Baudrillard names “hyperreality.”[3] In similar lineage, Jameson describes, “postmodern hyperspace,”[4] as a mutation in space that “transcends the capacities of the individual human body to locate itself, to organize its immediate surroundings perceptually, and cognitively to map its position in a mappable external world.” The “disjunction” between body and the built environment - in opposition to older modernist technologies that involved sensible velocity - subject individuals to become entangled in “global multinational and decentered communicational network.”[5] The invention of air conditioning and most importantly, the invention of the idea of “comfort” tied to active climatic control using mechanical systems (most notably, cooling), the relationship between objects and the environment transform. Baudrillard lists three tendencies: “an ever greater formal and operational abstraction of elements and functions and their homogenization in a single virtual process of functionalization; the displacement of bodily movements and efforts into electric or electronic commands, and the miniaturization, in time and space, of processes whose real scene (though it is no longer a scene) is that of infinitesimal memory and the screen with which they are equipped.”[6] The changed context of climatic control allowed application of “theories of management, based in the value of automation,” to be applied to all the environments where human occupants inhabit. The technical knowledge that pertained to regulation was thus given a distinct form: a collection of thermostats, ventilators, ductwork, and electrical circuitry that produced an internalized network of control.[7]

Victor Gruen and Billie Eilish: The Birth of Suburban Leisure and Malls

“Billie Eilish in a Mall”

Figure 4: Therefore I Am, Billie Eilish (2020)

Billie Eilish’s Therefore I Am music video[1] starts with the zoomed in shot of Billie’s feet on glossy tiles. The shaky handheld camera follows Billies’ footsteps as she hops onto an escalator. The setting remains unspecific, cloaked in the anonymity of a sterile white tunnel. Yet, as Billie rounds the corner, the glow of a PacSun logo flickers into view. The whimsical typography of Justice, the glistening white floors, and the cool translucency of bluish guard rails evoke a space so ubiquitous it verges on the uncanny: the shopping mall.

[1] Billie Eilish, “Therefore I Am (Official Music Video),” YouTube video, 3:16, posted November 12, 2020

The glossy surfaces and sterilized hues dissolve any sense of particularity, rendering the mall as both everywhere and nowhere. As one of the Hollywood's most recognized superstars runs through the empty hallways of the mall, grabbing a pretzel from the counter of Weltzel’s Pretzel and a bag of chips from Chipotle, the viewer is transported to a mall that could be in their own suburb, or any suburb at all. It is not the specificity of the space that captivates but its universal grammar of American malls: the viewer might not know how far the mall is from their own home, but they know the food court will be somewhere on the second floor, Target will be at the end of the corner, and Cheesecake factory will be somewhere near the exit. This is a space that elicits déjà vu, through its haunting sameness eroding any claim to uniqueness of the white collar person’s memories.

“Introvert Center: Southdale Center”

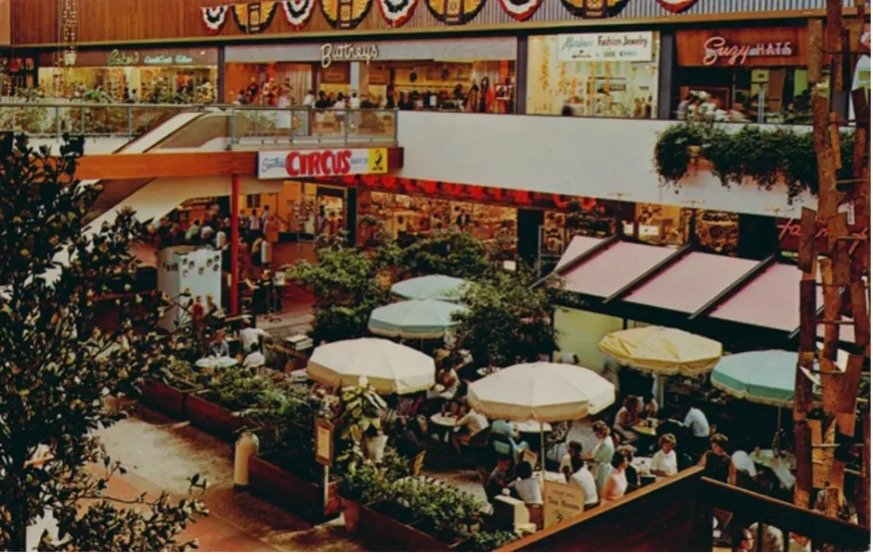

Figure 5: Southdale Center (1956), Minnesota Historical Society

[1] William Severini Kowinski, The Malling of America: An Inside Look at the Great Consumer Paradise, 1st ed.

In 1956, Southdale Center, America’s first fully enclosed shopping center, opened in Edina, Minnesota. Southdale was the architect Victor Gruen’s experiment: a simulation of the old European city transplanted into burgeoning suburban sprawl of America. Two major department stores on the opposite end were connected through an axis of atrium with a central garden at the midpoint. This enclosed space allowed a creation of a new biome - a synthetic paradise of hanging plants draped from balconies, fishponds, towering artificial trees, and a 21-foot cage teeming with birds.[1] The enclosure offered a refuge from Minnesota’s extremes, allowing visitors to forget the suffocating humidity of summer and the biting -30°C cold of winter. With Sidewalk Cafe, a restaurant with umbrellas over the tables that spilled over to the atrium, and sitting areas around the central garden, pieces of the Gruen’s old world across the Atlantic ocean travelled to American Midwest.

No-sweat Architecture

The architecture of erasure and indoctrination -"no-sweat" architecture — what Baudrillard calls “hyperreality,”[1] Jameson calls “postmodern hyperspace,”[2] and Rem Koolhaas calls, “junkspace,[3]” represents a transition in the spaces designed for the white-collar world in the latter half of the 20th century. The occupants of no-sweat architecture, from a suburban mall to an office park, to X, are never expected to be exposed to extremity of psychological or physiological conditions. In the new neutrality of their environment, their minds are indoctrinated to the new doctrine of white collar, the “vain quest for utopic equilibrium,” or the “middle course, at a time when no middle course is available.”

Their idea of a success and freedom are an illusory course in an imaginary society. William Whyte describes in his book on the emerging class of the white-collar, The Organization Man, “whatever history they have had is a history without events; whatever common interests they have do not lead to unity; whatever future they have will not be of their own making.” [4] Their spaces reflect this condition: the optimally conditioned spaces where choice feels abundant but is ultimately curated to be friction-less, where lives are shaped by unseen hands and predetermined paths.

We have used shopping mall as an example of a no-sweat architecture in the previous section. The alienation within consumer society became a platform for corporate advertisement and “spectacles.” According to Baudrillard[5], “as long as there is alienation, there is spectacle, action, scene. It is not obscenity - the spectacle is never obscene.” The alienation creates a black box relationship (one sided or two sided), where images are projected onto the opaque surfaces. Spaces of alienation that no-sweat architecture creates lack the visibility of the obscenity.

[1] Baudrillard, "The Ecstasy of Communication," 128.

[2] Jameson, Postmodernism, 81.

[3] Koolhaas, "Junkspace," 175.

[4] Whyte, William H. The Organization Man. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1956.

[5] Baudrillard, "The Ecstasy of Communication," 129.

[6] Baudrillard, "The Ecstasy of Communication," 129.

[7] Baudrillard, "The Ecstasy of Communication," 129.

Obscenity begins with the absence of spectacle, where all becomes transparency and immediate visibility, when everything is exposed to the harsh and inexorable light of information and communication.[6] The machines, from ducts and pipes of HVAC systems to intangible machines of global supply chains to marketing meetings, lie hidden from the sleek and chill surfaces. “It is our only architecture today: great screens on which are reflected atoms, particles, molecules in motion. Not a public scene or true public space but gigantic spaces of circulations, ventilation and ephemeral connections.”[7]

Bibliography

"40,000 Visitors See New Stores; Weather-Conditioned Shopping Center Opens." The New York Times, October 9, 1956.

"Southdale Center Has Own Community." Minneapolis Sunday Tribune, October 7, 1956

American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE). ANSI/ASHRAE Standard 55: Thermal Environmental Conditions for Human Occupancy. Atlanta, GA: ASHRAE, 2010.

Archambault, J. S. "Sweaty Motions." American Ethnologist 49, no. 3 (2022): 332–344.

Barron, James. “Before Anyone Complained About the Air-Conditioning, an Idea.” New York Times, 2012.

Baudrillard, Jean. "The Ecstasy of Communication." In The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture, edited by Hal Foster, 126-134. Port Townsend, WA: Bay Press, 1983.

Buffalo Forge Co. Apparatus for Treating Air. US Patent 808,897, filed September 16, 1904, and issued January 2, 1906. Expired January 2, 1923.

Buffalo Forge Co. Method of Humidifying Air and Controlling the Humidity and Temperature Thereof. US Patent 1,085,971, filed December 1, 1907, and issued February 3, 1913. Expired February 3, 1931.

Carrier Engineering Corporation. The Story of Manufactured Weather, by the Mechanical Weather Man. [New York: Carrier Engineering Corporation], 1919.

Carrier, W. H.Rational Psychrometric Formulae: Their Relation to the Problems of Meteorology and of Air Conditioning Trans. ASME ASME. January 1911 33 1005–1039

Eilish, Billie. “Therefore I Am (Official Music Video).” YouTube video, 3:16. Posted November 12, 2020. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RUQl6YcMalg.

Forsyth, Ann. "Defining Suburbs." Journal of Planning Literature 27, no. 3 (2012): 270–281.

Jameson, Fredric. Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham: Duke University Press, 1991.

Kallipoliti, Lydia. “Closed Worlds, Bubbles, and Voluntary Containment.” The Architecture of Closed Worlds, 2018.

Kheirabadi, Masoud. Iranian Cities: Formation and Development. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1991. 36. ISBN 978-0-292-72468-6.

Kowinski, William Severini. The Malling of America: An Inside Look at the Great Consumer Paradise. First edition. New York: William Morrow and Company, 1985.

Life. Vol. 16, no. 4 (January 24, 1944): 104 pages. ISSN 0024-3019.

Mills, C. Wright. White Collar: The American Middle Classes. New York, NY, 2002.

Osman, Michael. Modernism's Visible Hand: Architecture and Regulation in America. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2018.

Roberts, Kate. "Southdale Center." MNopedia. Minnesota Historical Society.

Steemers, Koen, and Simos Yannas, eds. Architecture, City, Environment. Cambridge Programme for Industry, Martin Centre for Architectural and Urban Studies. London: James and James, 2000.

Teitelbaum, Eric, Clayton Miller, and Forrest Meggers. 2023. "Highway to the Comfort Zone: History of the Psychrometric Chart" Buildings 13, no. 3: 797.

Whyte, William H. The Organization Man. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1956.

Yagoglou, C. Heat given up by the human body and its effect on heating and ventilating problems. Am. Soc. Heat. Vent. Eng. 1924, 30, 597–609.