The Value of the Notebook

by Gert Duvenhage

Gert Duvenhage is a designer from South Africa currently pursuing his SMArchS AD degree. With an intent on re-evaluating our understanding of the boundaries of the architectural discipline. He focusses on finding solutions to intricate and complex problems through unrestricted and fluid approaches. Drawing from unfamiliar interests rather than applying a fixed style, he lets each problem reshape his process.

His previous work has delved into the intricacies of crime-scene sites as places of performance, religious places for the secular, self- funded and executed exhibitions meditating on art and design as a connected heritage, multi-site rejuvenation for sensitive and displaced archaeologies, research into co-operative breeding mammals in Sub-Saharan Africa, Ai and large language models for translating images to music, low earth orbit space-wearables and thermal imaging devices.

Have you noticed that when you sketch, you start to understand the subject more deeply? When you make a note of something, you find peace in knowing that the information is stored elsewhere. Sketching is a conduit for miraculous things to happen. You start understanding each part as a component in a whole and their beautiful relationships with one another. Think of the sketches of Darwin or von Humboldt. Many others have found the value of documentation, yet we might not be taught as directly as we’d like.

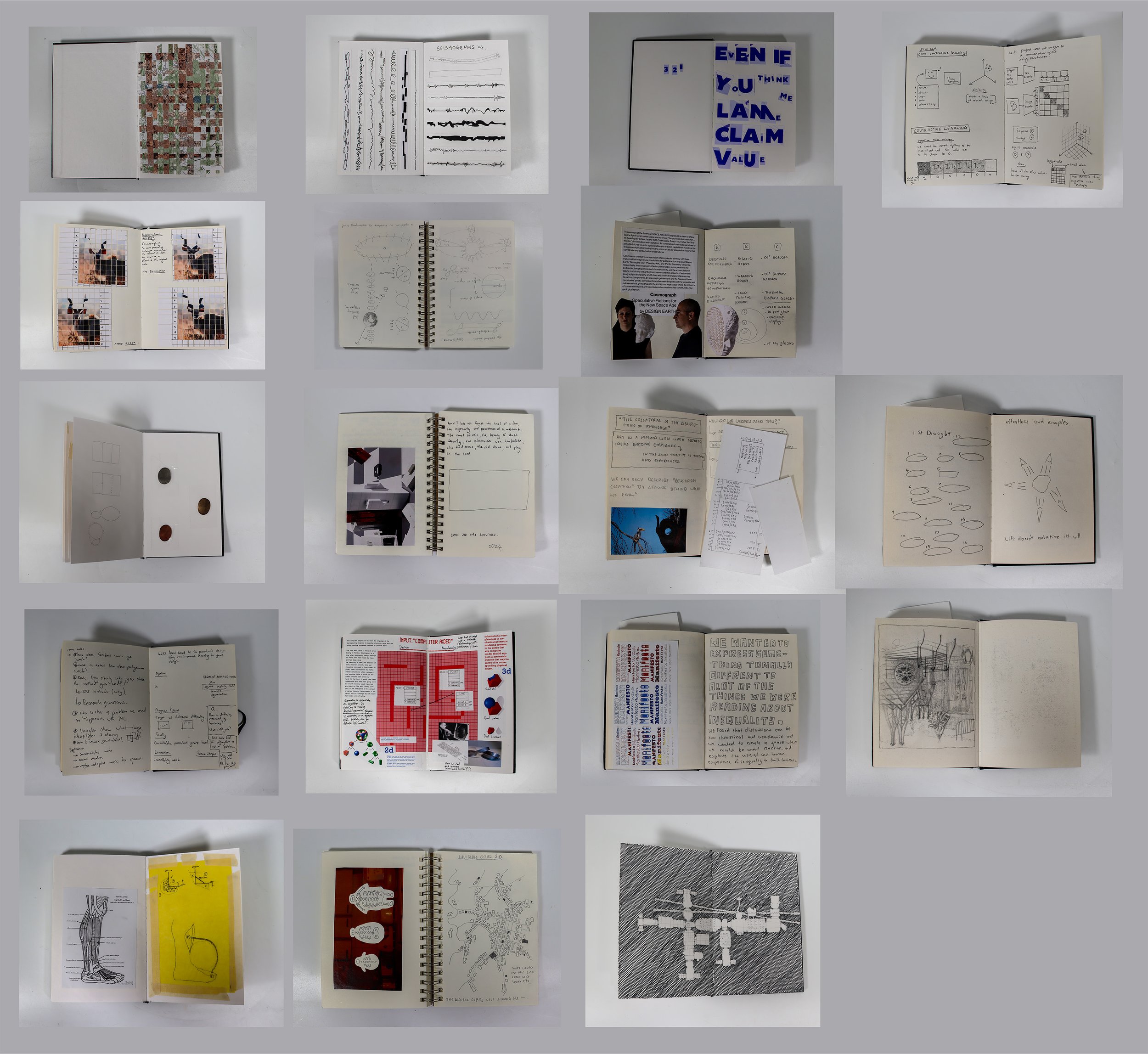

During my first year of architecture school, we were introduced to this practice through a very small black sketchbook called a carnet. “Use this to sketch in,” were words that offered little comfort in a year defined by newness. A year lived in the shadow of uncertainty. As we continued to work in our books, we started to understand more and more. Just like we do when we sketch something, the uncertainty starts to fade and is replaced by value. For me, the notebook continues to reveal its utility in these ways, even if its meaning isn’t restricted to these.

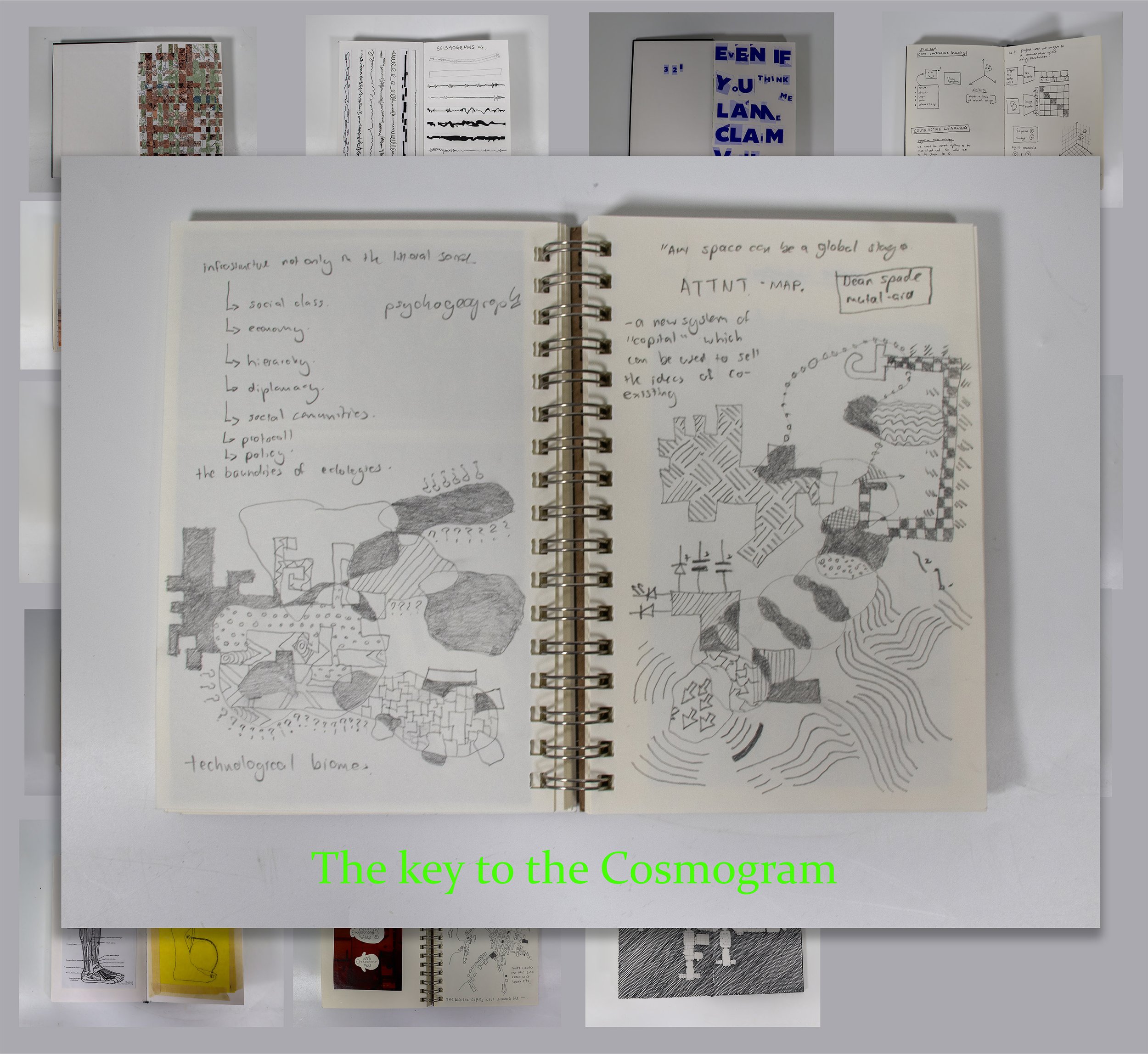

Notebook as space of exploration

We use the design process to comprehend and explore ideas. The notebook becomes a platform where we can do so with no self-scrutiny. Its pages become a generator, a quick and honest generator at that. It is a place where your 10-second gesture drawing cohabitates with notes on coding, a grocery list, and ideas for a practice. Here, we can design without consequence, or we can set our own consequences. We can parameterize, doodle, write, experiment, superimpose, weave, iterate, sketch, take notes, make spelling mistakes, scribble, and critique. We can do so with the touch of a brush, the stroke of a pencil, or the dab of a glue stick.

Yes, of course we sketch in a sketchbook. After all, that is what the name implies, but these blank pages can serve any purpose you assign to them. I credit my fourth-year theory of architecture professor, Dr. Hendrik Auret, for opening my eyes to the utility of a carnet. He taught me that what is exercised here is the ability to read with intent and summarize with imagination. His advice was to read essays and summarize them using drawings in small sketchbooks: on a single spread, keep half for description and the other half for a sketch, and do not restrict yourself to a single medium. In doing this, you start to formulate ideas and opinions from works of text.

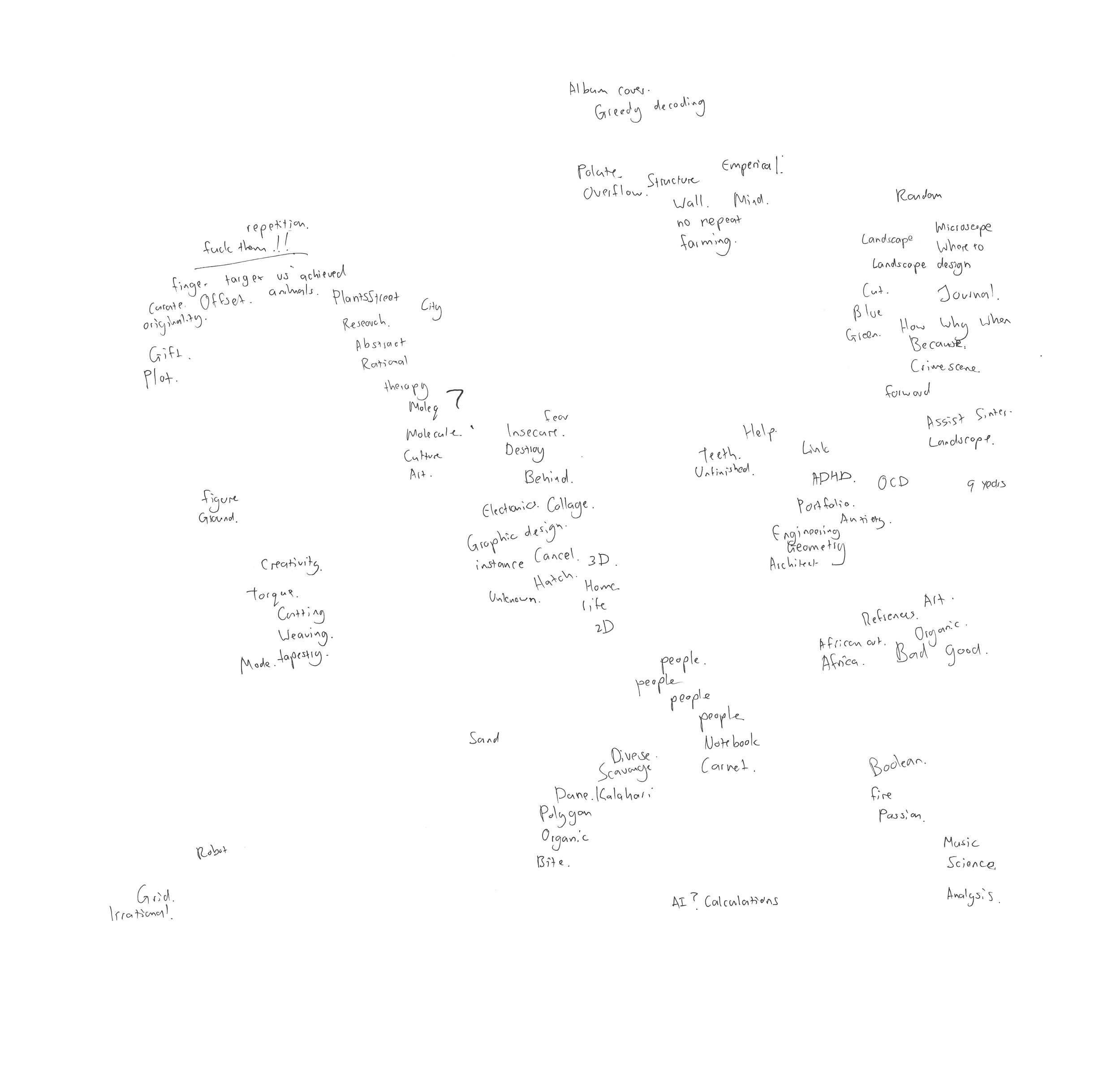

My advice, to you and maybe also to my future self, is to read. Read anything. Summarize it, take what is interesting, and plot it in your book. Imagine it as a two-minute project proposal. Build your own repository of ideas and positions through ideation. You’ll need a lexicon in the future. Few things I am able to guarantee, but here I can faithfully promise surprise and dividends on your input.

Notebook as space of simmering

As we read, we consume but do not always process information with intent. Sometimes, at a glance, things can seem foreign or even unrelated to architecture. In a field obsessed with aesthetics, we often discard ideas easily based on looks or preconceived perceptions. What to make of a documentary on tightrope walking? Perhaps if I had patience with my ideas, I would recognize a false superficiality.

Here I am proposing a recipe for a well-cooked idea: In the notebook, leave ideas, projects, sketches, thoughts, and notes to cook. Let them boil and develop. Here, keeping a watchful eye is less important than one might think. Leave them somewhere without deadlines or critics. Place them on pause. You can be your own future critic, and many times that is more than enough. The notebook sets aside space for us to look back on our work without graded judgment, knowing the world isn’t worse off because of it. You haven’t failed; you have only learned and done.

During this simmering process, an anticipation and hunger for “it” starts to develop, whatever you have set to bake between the pages of your book. You notice it on the kitchen windowsill, and it draws you in with its mystery. In a few days, you’ll look at it with fresh eyes. You might look at bad ideas and find them attractive. It is all natural, really. But maybe you can finally start to see them for what they truly are.

Notebook as RAM and SSD

Yet when we design, we often quickly and unexpectedly stumble upon ideas. They might not have a place for the moment, but they do need space to rest. Sometimes they start on a computer screen, on the street, or in a dream. That does not make them unworthy of being included in our libraries. In fact, those lightning strikes should be articulated within our Random Access Memory in our notebooks. Suddenly, they are rendered accessible in our often overly fleeting, input-saturated, and attention-deficit minds.

But RAM isn’t just our short-term memory; it is also the absence of erasure. The notebook facilitates the transfer from our volatile RAM to our long-term storage—our SSD. These projects journey with us; they are important to our source code and might even stage themselves beyond the confines of our pages, eventually or immediately. Maybe they don’t make it into our portfolios because they are uncooked or risky to serve, but they deserve reverence somewhere. Hopefully, they will also remember their humble beginnings when they finally find the limelight.

RAM isn’t just a piece of paper. It’s also an arm you write on which then becomes a tattoo. Or a piece of paper you scribble on which is then glued down later. It is the notepad on your phone printed out and edited on Photoshop. A message you send and take a screenshot of, an email you send to yourself, or telling a friend to remind you later. This short-term documentation allows us to regain a sense of control and connectedness to our work. These might all be intermediaries, or sadly final destinations, but the practice of accessing our RAM is crucial for letting ideas find their final resting place.

Notebook as space of therapy

For me, perhaps the most profound impact the notebook has had isn’t on my identity as a designer at all. It is the realization that we can use a notebook to cope with design anxiety or obsessions. You can use it to get rid of design compulsions. The design process is fraught with negative emotions. When finding yourself trapped, feeling like you haven’t achieved much, a quick sketch in the notebook is a rush of dopamine to reward yourself with progress, even if it is personal. When you are depressed, stressed, or sad, take a glance at your stacks of journals. Write what you feel, it is, after all, a journal; it can be whatever you want it to be. Design is definitely not isolated from our emotions; if we can understand both side by side, we become more wholesome and effective as individuals and as creators.

I often become allured by design choices which I know are safe and tried. These might be from my own discography of designs, which sometimes can be trendy and untasteful. A fear of becoming a designer I detest, or not being creative enough, sneaks up on me. Inevitably I land on the same question: Where do you find inspiration? Perhaps the question should be when do you find inspiration? For me, it might be an idea I’m having when I’m busy with something totally different. It’s fleeting, and there is a chance that I will forget it when I walk through the next doorway. Here, your lexicon and catalogue of ideas can offer solace.

Simultaneously and paradoxically, I also like to not place myself in a box. I want the freedom to explore and be whichever designer I want to be, even if it includes previous iterations of myself. To keep myself in check, I use the notebook as a promise and a principle. Here, the notebook becomes a platform for all of these identities to co-exist and find peace.

Looking back on these books, I find myself feeling that there should be more of them, and more to them. They seem strangely empty. Maybe this is a sign to revisit them more often. Fill your notebook, even if it is with one word, one image, or one sketch on a page. When you don’t know what to do next or where to start, yet you still want to remain productive, glue a few images in its pages and feel a sense of accomplishment. You’ve done something for yourself, and you’ve finished doing it. When you look back on your work, don’t do so with disgust, but with utility and empathy. I am not claiming that the notebook is a miracle cure.

Just that it might need some dusting off.